INTRODUCTION

The immunobullous diseases are characterised by cutaneous and mucosal blisters due to pathogenic antibodies which target structural antigens in the skin.

The keratinocytes of the epidermis are held together by a family of proteins called the desmosomes.

In superficial blistering diseases (eg pemphigus vulgaris) these proteins can be targeted and you get superficial blistering

The most clinically relevant tends to be the transmembrane proteins desmoglein 1 and 3

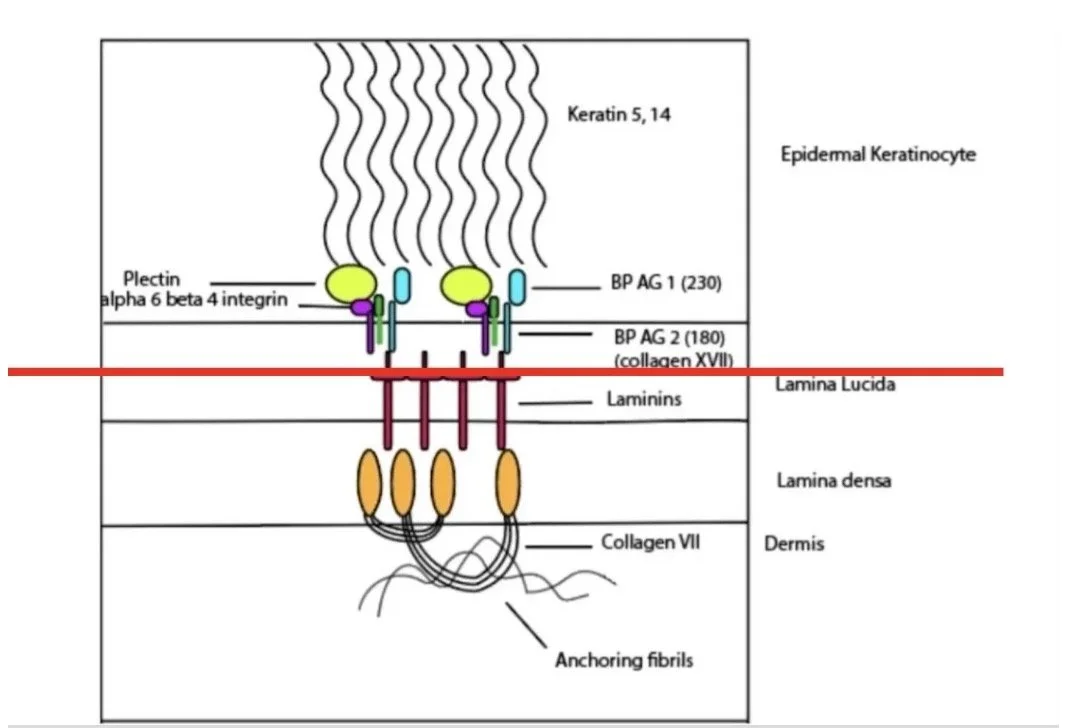

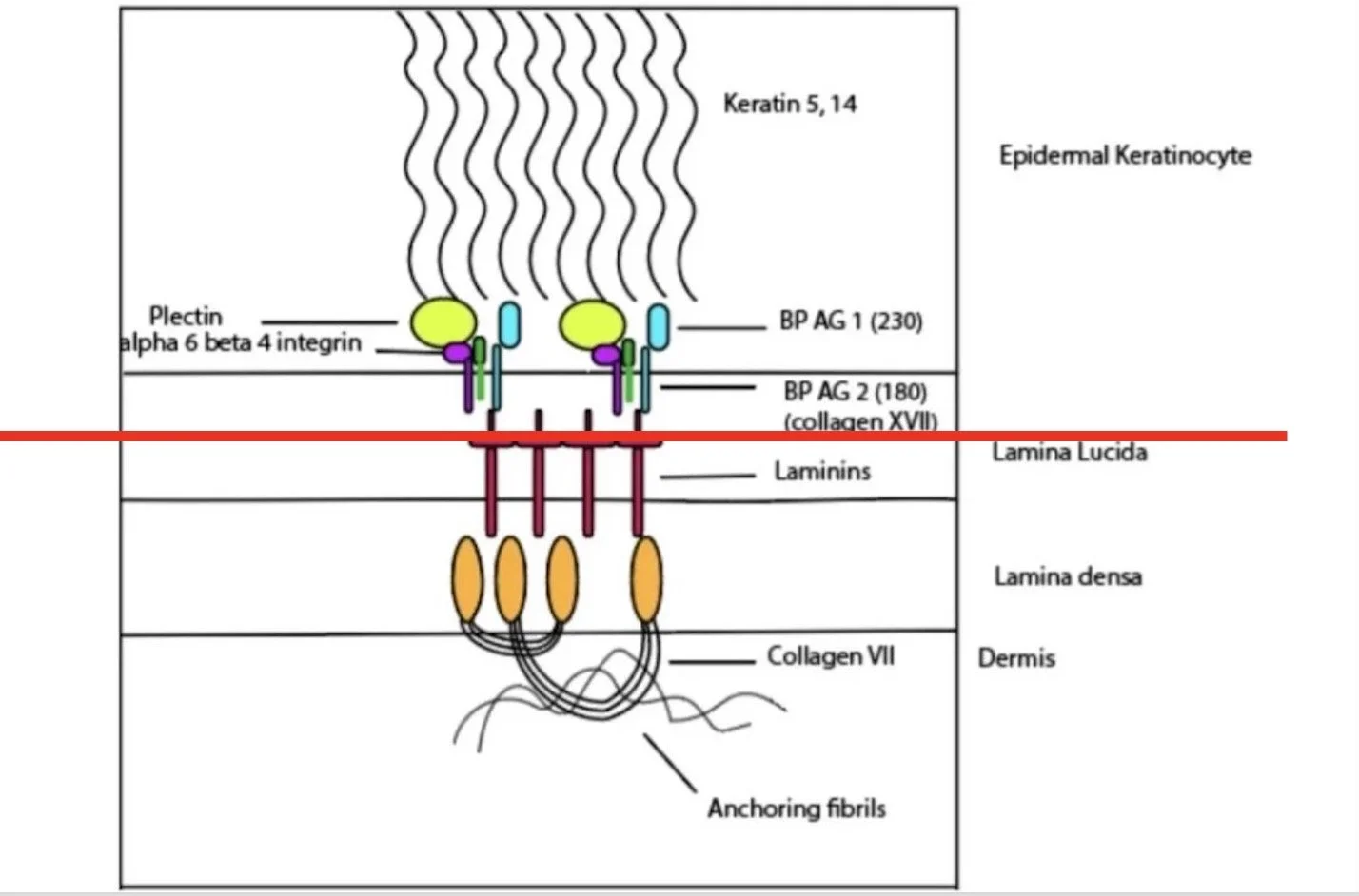

In deeper blistering disorders (eg pemphigoid disorders), the split involves the basement membrane zone:

The inferior part of basal keratinocytes

The basement membrane (lamina lucida and lamina densa)

The upper dermis

The hemidesmosomes are the collection of proteins involved in keeping the basal keratinocytes attached to the extracellular matrix in the dermis

The clinical picture depends on the depth of blistering:

High in the epidermis (pemphigus diseases): shallow blisters that often present as erosions rather than intact blisters

Around the dermo-epidermal junction (pemphigoid diseases): much more tense blisters

At or below the lamina densa: tense blistering that often results in scarring

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS BLISTERING RASH

Blistering Disorders

Differential Diagnosis Overview

- Pemphigus vulgaris

- Pemphigus foliaceus

- Paraneoplastic pemphigus

- IgA pemphigus

- Bullous pemphigoid

- Mucous membrane pemphigoid

- Pemphigoid gestationis

- Dermatitis herpetiformis

- Linear IgA disease

- Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita

- Epidermolysis bullosa (not acquired form)

- HSV

- Herpes zoster

- Hand-foot-mouth disease

- Bullous impetigo

- Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

- Severe cellulitis/necrotising fasciitis

- Bullous tinea

- Bullous scabies

- Contact dermatitis (e.g., severe hair dye allergy)

- Phyto-photo dermatitis (plant dermatitis)

- Vesicular hand dermatitis

- Bullous lupus

- Severe vasculitis

- Oedema blisters (e.g., gross oedema in legs)

- Trauma - burns, friction, scalds

- Insect bites

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

A standardised approach should include:

Clinical assessment: History, examination, disease activity assessment

Biopsy for H&E (lesional skin)

Biopsy for direct immunofluorescence (peri-lesional skin, within 1cm)

+/- Blood tests: Indirect immunofluorescence +/- ELISA

SKIN BIOPSY

For H&E:

Take a 4mm punch biopsy from lesional area containing a bit of blister and surrounding skin

Send in standard formalin pot

For Direct Immunofluorescence (DIF):

Take a 4mm punch from peri-lesional normal skin (within 1cm of active blister)

Preferably from non-inflamed skin

Send in Michel's medium

HISTOLOGY (H&E)

H&E by itself can’t give you a full diagnosis but it can give you some clues to the diagnosis based on:

Level of split:

Subcorneal

Intraepidermal

Subepidermal

Nature of inflammatory infiltrate:

Neutrophils

Eosinophils

Lymphocytes

Cell-poor

DIRECT IMMUNOFLOURESCENCE (DIF)

DIF is the gold-standard diagnostic tool for immunobullous disease

It allows us to visualise the immune system attacking the skin by making the autoantibodies glow under a microscope

This is performed on tissue from a biopsy

Principle:

Sample: Performed on a biopsy of perilesional skin

Mechanism: Laboratory antibodies "tagged" with fluorescent dye are added to the tissue.

Binding: These lab antibodies seek out and idenify antibodies/proteins (IgG, IgM, IgA, C3 +/- fibrinogen) which is bound to the tissues

Result: Under a fluorescent microscope, the "tagged" areas glow a bright green and we can see the patterns of where and how they are deposited

Result:

DIF is used to narrow down the diagnosis according to the deposited immunoglobulin subclass and the binding pattern seen

However, it provides limited information on the specific antigens that are targeted

Pemphigus diseases (superficial):

Antibodies bind to keratinocytes

Forms a 'chicken wire pattern'

Intercellular deposition of IgG +/- C3

Pemphigoid diseases (deep):

Antibodies bind linearly to the dermo-epidermal junction (DEJ)

Linear deposition of IgG +/- C3 at the basement membrane zone

Dermnet: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/directimmunofluorescence/

Dermatitis herpetiformis:

Granular or fibrillar deposition of IgA +/- C3 in dermal papillae

Dermnet - https://dermnetnz.org/topics/dermatitis-herpetiformis

Linear IgA disease:

Linear deposition of IgA +/- C3/IgG at basement membrane zone

Intensity of IgA fluorescence higher than IgG and C3

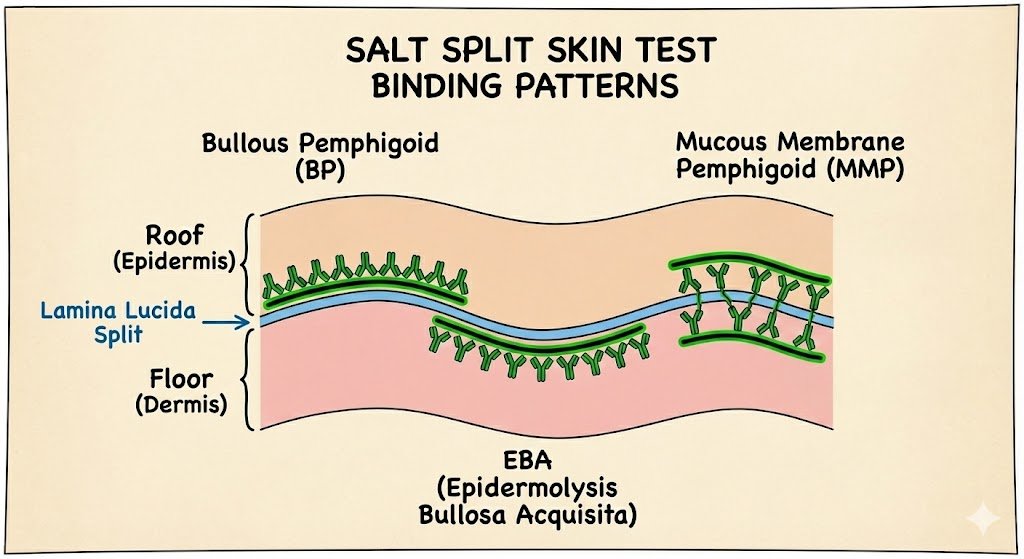

SALT SPLIT SKIN TEST

Helps differentiate bullous pemphigoid from other sub-epidermal blistering conditions.

The biopsy is incubated in 1mol/L salt, which causes a split at the lamina lucida (the 'loose lucida').

In Bullous Pemphigoid

Antibody (usually IgG) found on the blister roof (epidermal side)

In EBA (Collagen VII):

Antibodies found on blister floor (dermal side)

In Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid:

Deposition can be to roof, floor, or mixed pattern depending on antigens targeted

Roof - BP 180, 230, α6β4 integrin

Floor - Laminin 332, Type VII collagen

SERRATION PATTERN

Looking at the serration pattern refines localization beyond what salt split skin shows.

The salt split separates at the lamina lucida with the following conditions staining on the dermal side:

Laminin γ1 (p200 pemphigoid)

Anti-laminin 332 (associated with mucuous membrane pemphigoid with higher risk of internal malignancy)

Collagen VII (EBA, Bullous Lupus)

When examining the linear fluorescence on salt split skin at higher magnification, the serration pattern of the undulating basement membrane zone can help distinguish between these deeper conditions

It separates conditions based on whether the antigens at/above the lamina densa or below

Recap:

Most helpful when salt split shows dermal-side binding (floor) and need to differentiate the conditions further

Memory aid: 'u' for ‘under’ the lamina densa

BLOOD TESTS

Blood tests can be performed for the serologic detection of antibodies

The conventional method performed is:

Initially do indirect immunoflourescence (IIF) microscopy as a screening test

This can be followed by a more antigen-specific serologic assay (eg ELISA) based on the clinical suspicion and IIF screening results

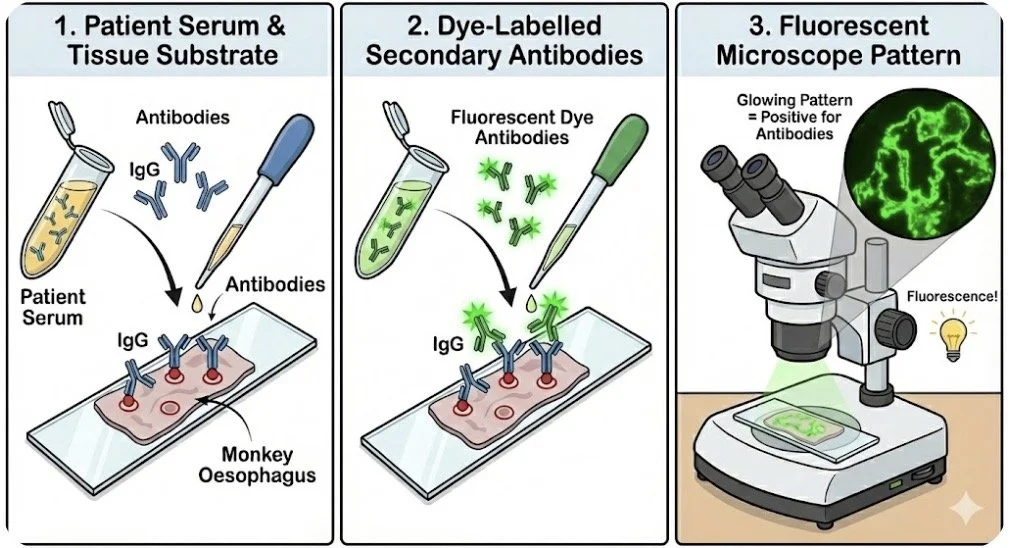

INDIRECT IMMUNOFLOURESCENCE

Detectes circulating antibodies in serum

Very sensitive - good for screening

Not as specific for determining causative antibody as ELISA

IIF is a technique used to detect circulating antibodies in a patient’s serum blood test:

Antibodies/complement (eg IgG, IgM IgA, C3 ) from the patient’s serum (primary antibodies) bind to the target molecules (the substrate) in pre-prepared tissue samples (eg monkey oesophagus)

Then antibodies labelled with dye bind to the above antibodies

The pattern of staining then seen using a fluorescent microscope

Choice of substrate tissue to use may depend on clinical suspicion of the suspected disease

For instance, classic prepared tissues which are better for certain diseases are:

Sub-epidermal blistering diseases - Normal human skin

Pemphigus vulgaris - monkey oesophagus - monkey oesophagus has high expression of Dsg 3

Pemphigus vulgaris - moneky oesophagus - a monkey acting vulgar

Pemphigus foilaceous - guinea pig oesophagus - good for dsg 1

(think of a guinea pig running in foliage)

Pemphigus foliaceous - guinea pig oesophagus - a guinea pig roaming the foliage

Paraneoplastic pemphigus - rat bladder - plakins (envoplakin, periplakin, desmoplakin) are highly expressed in bladder

ELISA

To achieve a more precise diagnosis, clinicians can identify antibodies directed against specific target antigens using ELISA (Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay), Immunoblotting, or monospecific Indirect Immunofluorescence (IIF).

ELISA is the most widely used method for targeted antibody detection because it:

Identifies Specific Antigens: It confirms the exact molecular target (e.g., Dsg 1 vs. Dsg 3).

Quantifies Antibody Levels: Unlike standard IIF, ELISA provides a numerical value, making it highly effective for monitoring disease activity and response to treatment.

The following antigens are routinely tested via ELISA at regional centers like St. John’s Institute of Dermatology:

Desmoglein 1 and 3: For Pemphigus variants.

BP180 and BP230: For Bullous Pemphigoid.

Collagen VII: For Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita (EBA).

In labs in the USA they can perform more specific tests using specialised techniques

Laminin 332 - Mucosal membrane pemphigoid associated with solid organ cancer

Laminin γ1 - p200 pemphigoid

PEMPHIGUS: AN OVERVIEW

Pemphigus is a group of autoimmune bullous diseases primarily affecting the skin and/or mucous membranes, charachterised by antibody-mediated acantholysis

Acantholysis refers to the separation of keratinocytes due to disruption of intercellular bridges (desmosomes)

Pathophysiology

Keratinocytes are held together by various proteins including proteins called desmosomes. The most clinically relevant desmosomes are desmoglein 1 and 3

Desmoglein 1:

Most abundant in superficial epidermal layers (stratum granulosum/corneum)

Present in high concentrations in skin

Found in lower amounts in mucosal tissues

Desmoglein 3:

Highly abundant in mucous membranes

Present in deeper layers of epidermis (basal and lower spinous) but at lower levels than Dsg1

The Golden Rule: If Dsg 3 is involved, it is Pemphigus Vulgaris.

Pemphigus Foliaceus (Dsg 1 only):

Targets 1 antigen and predmoninantly 1 organ—the skin.

Since Dsg 3 is still working in the mouth, the mucous membranes tend to stay healthy.

Pemphigus Vulgaris (Dsg 3 +/- Dsg 1):

The mucous membranes are usually affected (where Dsg 3 is the primary "glue")

But the skin can also be affected (especially if Dsg 1 affected) and this can also be very severe

Pemphigus Epidemiology

Incidence: 0.5-8 cases per million in Europe

Peak age: 40-60 years (rare under 20 years)

Gender: Slight female preponderance

Ethnicity: Higher frequency in people of Jewish ancestry (particularly Ashkenazi Jews)

Pemphigus vulgaris and foliaceous collectively account for 90-95% of all pemphigus cases

Genetics:

HLA alleles are strongly associated with an increased risk of pemphigus

HLA-DRB104:02 and DQB105:03 most significant

Pemphigus patients may have increased frequency of -

Haematological malignancy: CLL, NHL, Multiple myeloma

Solid organ cancers: oropharyngeal, colon

Autoimmune diseases: Thyroid disease, rheumatoid arthritis

Drugs:

Drugs containing a thiol group have been implicated (penicillamine, captopril)

PEMPHIGUS VULGARIS

Charaterised by antibodies against desmoglein 3 and/or desmoglein 1

The presence of anti-Dsg3 antibodies means mucosal involvement is common and often predominant, as Dsg3 is highly abundant in mucous membranes

When both anti-Dsg3 and anti-Dsg1 antibodies are present, patients tend to experience severe skin disease in addition to mucosal lesions

The acantholysis in PV occurs just above the basal layer of the epidermis, leading to a suprabasilar split

Clinical presentation:

Cutaneous Features:

Shallow, fragile blisters that rupture easily

Leading to erosions and crusting

Initially appear on scalp, face, and shawl-like distribution on upper central torso

Can spread widely

https://dermnetnz.org/topics/pemphigus-vulgaris

Mucosal involvement:

Present at presentation in 50-70% of cases

Increases to 80-90% with time (some series report 100%)

Painful, shallow erosions with irregular borders

Erosive gingivitis common

Most commonly affected intra-oral sites:

Gingiva (80%)

Buccal mucosa (58%)

Palate (26%)

Tongue (15%)

Laryngeal involvement:

Causes hoarse voice, requires urgent ENT review due to risk of oedema and erosions

Ocular involvement:

Crusted erosions on eyelid margins, conjunctival erythema, injection and swelling

Nasal mucosa:

Painful erosions, epistaxis

Genitalia:

Painful erosions

Investigations:

Skin/mucosal biopsy:

For H&E:

Lesional area with bit of blister and surrounding skin

For DIF:

Cutaneous: Peri-lesional area (within 1cm)

Oral disease: can take from normal buccal mucosa (usually sufficiently reliable)

https://dermnetnz.org/topics/pemphigus-vulgaris-pathologyhttps://dermnetnz.org/topics/pemphigus-vulgaris-pathologyPEMPHIGUS FOLIACEUS

Pemphigus foliaceus results from antibodies primarily directed against desmoglein 1

As Dsg1 is most abundant in superficial layers of the epidermis and found in lower amounts in mucosal tissues, PF typically presents with predominantly cutaneous lesions and rare mucosal involvement

Split occurs high in the epidermis (subcorneal/granular layer)

Skin features:

Crusted and shallow erosions

Often in a seborrhoeic distribution (can sometimes resemble a seborrhoeic dermatitis)

Common areas: scalp, central chest, face, and mid-back

Intact blisters rarely observed (too superficial, rupture quickly)

Erosions generally less painful than PV but can itch/burn

Skin biopsy:

Take a biopsy of a blistered area which includes intact surrounding skin for H&E

Take a biopsy of a peri-lesional area (within 1cm) for DIF

Differential diagnosis intra-epidermal/sub-corneal split on H&E:

Pemphigus foliaceus

IgA pemphigus

Bullous impetigo

Sub-corenal pustular dermatosis

Staphylocccal scalded skin syndrome

Dermnet - indirect immunoflourescence

Endemic Pemphigus (Fogo Selvagem)

Endemic pemphigus, also known as fogo selvagem (meaning 'wildfire' in Portuguese), is essentially an endemic form of pemphigus foliaceus in Brazil

This if thoguht to be environmentally induced possibly from inset bites (eg from black flies).

Proteins left behind from the bite may induce immune mimicry leading to development of antibodies directed against the skin

The investigative findings (H&E, DIF, IIF and ELISA) are consistent with pempihigus foliaceous, showing antibodies against Dsg 1

PARANEOPLASTIC PEMPHIGUS

Paraneoplastic pemphigus is a rare but severe form of pemphigus with a poor prognosis

It is due to an abnormal B or T cell immne respoonse to an underlying malignancy

It is distinguished by antibodies to a wide range of epitopes, including desmoglein 3, desmoglein 1, envoplakin, periplakin, and desmoplakins, among others

Cytotoxic CD8 T cells also play a role which can lead to an interface dermatitis seen alongside acantholysis

This broad range of antibody targets and the cytotoxic T cell role contributes to the polymorphic clinical presentation we often see

Clinical features:

Patients often unwell

Typically begins with painful oral erosions, which can progress to severe and recalcitrant ulceration with pan-stomatitis and hyperplastic mucosa

Haemorrhagic cheilitis (crusted, bleeding lips) and severe ulceration in the oropharynx and genitalia are characteristic and often out of proportion to cutaneous involvement

Haemorrhagic cheilitis and severe oral erosions

The rash is often polymorphic with a variety of lesions and it can mimic other conditions like erythema multiforme, lichen planus or GVHD

Erosions over the torso

https://dermnetnz.org/topics/paraneoplastic-pemphigus

Lichenoid appearing rash on body

https://dermnetnz.org/topics/paraneoplastic-pemphigus

Lichenoid lesions: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/paraneoplastic-pemphigus

Other organs can be affected:

Lung involvement can lead to bronchiolitis obliterans (which can be severe)

GI tract can be involved

Associated cancers:

Lymphoma ≈ 40% of cases

CLL ≈ 30%

Castleman’s disease ≈ 10%

Castleman disease is a rare disorder that involves an overgrowth of cells in body’s lymph nodes

Most common form of the disorder affects a single lymph node (unicentric Castleman disease) usually in chest or abdomen

Multicentric castleman disease affects multiple lymph nodes throughout the body and has been associated with HHV 8 and HIV

Thymoma ≈ 6%

Spindle cell neoplasms ≈ 6%

Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinaemia ≈ 6%

Investigations

Dermnet - pareneoplastic pemphigusDermnet - paraneoplastic pemphigusManagement

To do….

PEMPHIGUS VEGETANS

Pemphigus vegetans is a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris (approx 2% of cases) which is chracterised by its clinical presentation rather than distinct antibody profiles

Clinically patients get vegetating, hyperkeratotic, papillomatous and fissured erosions

It typically affects flexural areas such as the axilla, groin and under the abdomen

They are often bacterial colonised and malodorous

Oral lesions are common and patients can get a distinctive cerebriform tongue

H&E: Histology may show eosinophilic abscesses or spongiosis with few acantholytic cells, which might not immediately look like typical pemphigus

DIF: Shows characteristic intercellular depoisition of IgG (chickenwire)

IIF: ELISA shows antibodies against Dsg 3 and desmocollins

PEMPHIGUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

(Also known as Senear-Usher syndrome)

Is a localised form of pemphigus foilaceous

Get scaly and crusted lesions across the malar area of the face and in other seborrhoeic areas

May remain localised for years or evolve into a more generalised pemphigus foilaceous

It is called pemphigus erythematosus as it shares immunologic features of both lupus erythematosus and pemphigus

Get IgG and C3 seen on cell surfaces of keratinocytes and in the basement membrane zone

May have serologic findings suggestive of SLE especially positive ANA

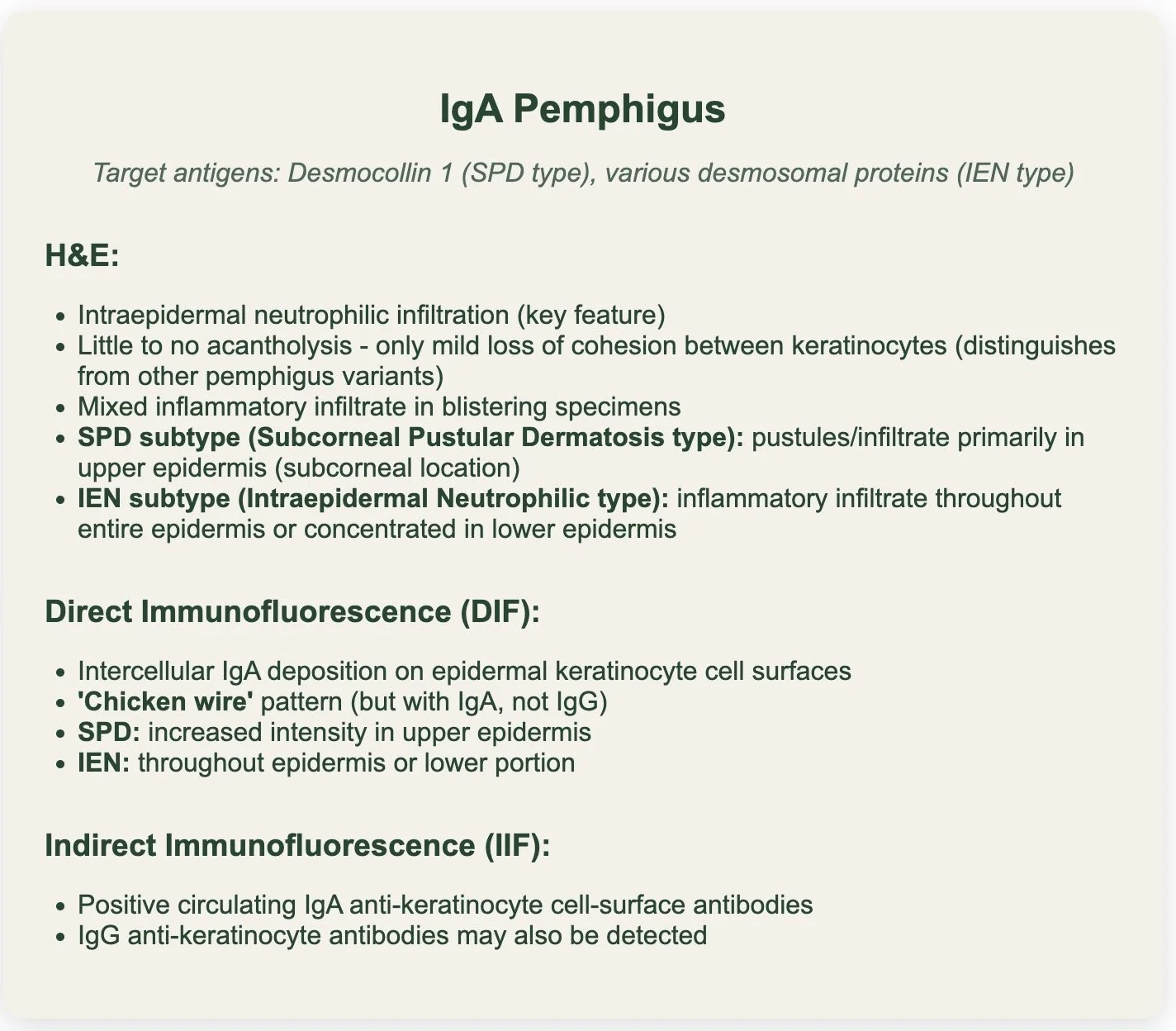

IgA PEMPHIGUS

There are two types of IgA pemphigus:

1. Subcorneal pustular dermatosis type (SPD)

2. Intraepidermal neutrophilic type (IEN)

Desmocollin 1 is the main antigen target overall particularly in the SPD sub-type

Dsg 1 and 3 can be targeted also

Both types associated with intercellular IgA deposits on immunoflourescence

There is NO ACANTHOLYSIS on histology (unlike pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigus foilaceous and paraneoplastic pemphigus)

Clinical:

SPD clinically presets as serpiginous vesicles and pustules

IEN classically presents as flaccid pustules and bullae arranged in an annular, polycyclic (sometimes referred as sun-flower like) arrangements usually in intertriginous areas

The pustules tend to quickly rupture and you get an annular crust over the plaque

Commonly affects flexural areas like axilla and groin but can be more widespread

Dermnet - IgA pemphigusAssociations:

Monoclonal IgA gammopathy

Multiple myeloma

Others reported: HIV, Sjogrens, RA, Crohn’s

Investigations:

H&E:

Intra-epidermal neutrophillic infiltration

Little to no acantholysis - have mild loss of cohesion between keratinocytes

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis subtype - increased intensity of IgA autoantibodies in the upper surface of the epidermis.

Intraepidermal neutrophilic - inflammatory infiltrates, primarily in either the entire or lower part of the dermis.

DIF:

IgA on epidermal cell surfaces

IIF:

Positive circulating IgA

Treatment options:

Steroids: topical and oral (0.5-1mg/kg)

Addition of Dapsone far superior to just steroids alone (dapsone often good for treatments with neutrophilic infiltrates)

Other agents: Colchichine, sulfapyridine, acitretin, PUVA

Less often: MMF, adalimumab (TNf-alpha is involved in activation of neutrophilic infiltration of epidermis so may hinder further progression of IgA pemphigus)

Ddx:

Subcorneal pustular dermatosis (aka Sneddon Wilkinson disease)

Sterile pustular lesions that erupt in cyclical patterns

Like IgA pemphigus the pustular lesoins coalesce in an annular pattern and burst to form crusted plaques

Similar area of distribution - groin, trunk, axilla and avoid mucous membranes

Histology shows perivascular infiltration of neutrophils and spongiosis

DIF negative for IgA

Pemphigus foliaceous

DIF is key - pemphigus foliaceous demonstrates IgG to DsG 1

Bacterial skin infections

Linear IgA Disease

Prognosis:

Much milder and limited disease compared to classic pemphigus

MANAGEMENT OF PEMPHIGUS

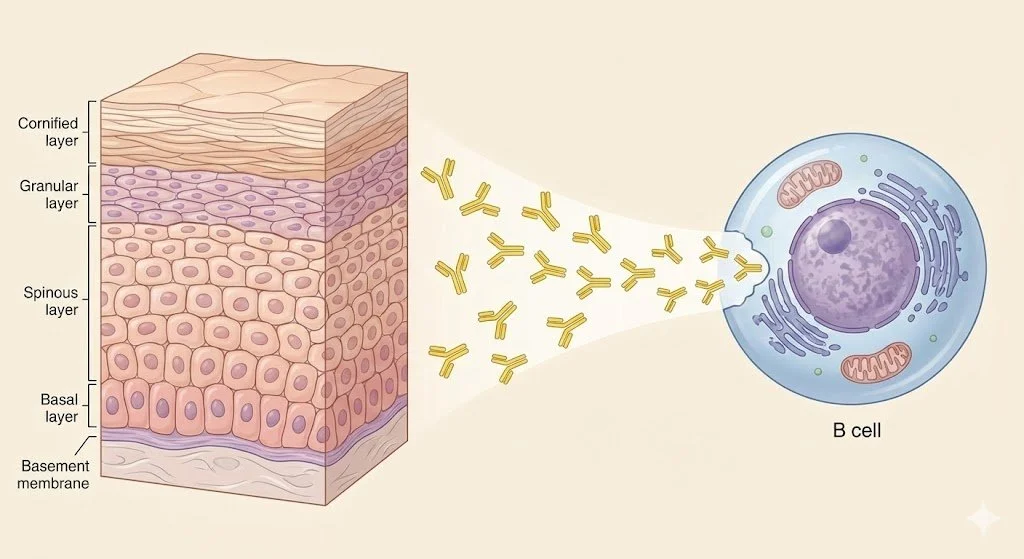

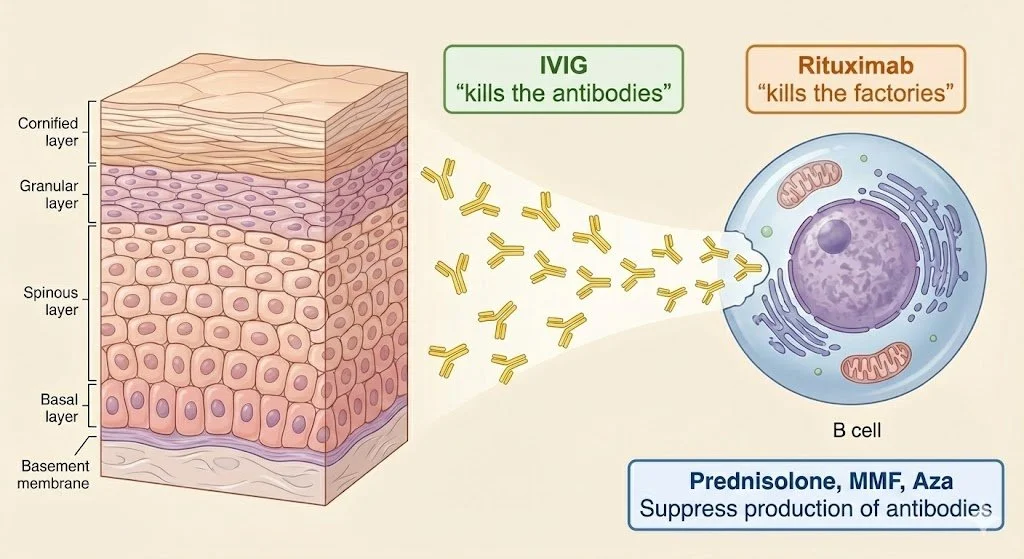

In pemphigus, B cells produce antibodies that target desmogleins, which are proteins that connect epidermal cells together. When considering treatment options, it's helpful to think of B cells as factories producing pathogenic antibodies:

Rituximab is an anti-CD20 antibody that directly targets B cells

Essentially 'destroys the factories' producing harmful antibodies

Other immunosuppressive agents (prednisolone, MMF, azathioprine) reduce the rate of antibody production by these cellular factories

IVIG promotes the destruction of circulating antibodies that have already been produced

There are UK and European guidelines regarding the management of pemphigus:

Enk A, et al. Updated S2K guidelines on the management of pemphigus vulgaris and foliaceus initiated by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020 Sep;34(9):1900-1913. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16752.

Harman KE, et al. British Association of Dermatologists' guidelines for the management of pemphigus vulgaris 2017. Br J Dermatol. 2017 Nov;177(5):1170-1201. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15930.

The key difference is the 2020 European guidelines recommend rituximab combined with tapering corticosteroids as a first-line treatment for moderate and severe pemphigus, whereas the 2017 British guidelines classify rituximab as a third-line treatment for refractory disease (however this was published prior to key trials demonstrating Rituximab’s efficacy as a first line treatment)

I attended a few clinics in St. John’s Institute Immunbullous clinic in 2024 and in general their practice was to trial a conventional systemic agent (eg MMF) for 3-6 months prior to commencing Rituximab

Please see https://www.stjohnsdermacademy.com/podcasts for a good reference podcast on Pemphigus vulgaris

I will discuss what they tend to do in St. John’s going forward but may be argument in Ireland to use Rituximab first line for moderate to severe pemphigus as per European guidelines

Initial skin care:

Topical agents

Antiseptic soap substitute if erosions present - Octenisan wash once daily (avoid Dermol 500 which is often used in UK due to increased irritant reactions)

Face - Moderate potency steroids (eg eumovate)

Body - Potent/super potent steroids (eg dermovate)

Oral agents

Betamethasone Solution:

Betamethasone 500mcg tablet dissolved in 10-20ml water

Use as mouthwash for 5 minutes up to QDS

Do not swallow

Flixonase Nasules:

Fluticasone propionate 400mcg contents in 10-20ml water

Mouthwash for 5 minutes up to QDS

Dermovate in Orobase Gel:

Apply directly to affected areas

Better for deeper, persistent lesions

Candida Prevention:

Add 1ml nystatin to steroid mouthwashes OR use standard antifungal therapy

Low threshold for treating oral candida

Systemic therapies for pemphigus:

Systemic Corticosteroids:

BAD Guidelines: Up to 1.5mg/kg daily

St. John's Approach: 0.5mg/kg daily (to minimise long-term exposure with associated complications)

Example Regimen (60kg patient):

Start: Prednisolone 30mg daily

Reduce by 5mg every 2 weeks down to 20mg

Slower reduction: 2.5mg every week/fortnight down to 10mg

Very slow reduction: 1mg weekly down to 5mg maintenance

Once reducing below 5mg need to consider a 9am cortisol +/- short synacthen test with gradual wean over severeal months to allow adrenal recovery

Ensure PPI and bone protection

Can consider pulse methylprednisolone in severe disease: 250-500mg IV daily for 2-5 days or as an adjunct to IVIG or rituximab

Conventional systemic agents:

Conventional immunosuppressive agents that tend to be used in pemphigus are azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil

Mycophenolate mofetil often used due to increased risk skin cancer associated with long-term exposure to azathioprine (azathioprine possibly has marginal superiority based on head to head trials)

Mycophenolate mofetil:

Dosing:

Start: 500mg BD

Increase to 1g BD within 2-4 weeks

Maximum: 2g daily (3g daily shows no superiority with more side effects)

Monitoring:

Pre-treatment: FBC, U&E, LFTs, pregnancy test, hepatitis B/C, HIV

Ongoing: Weekly × 2 weeks after dose increases, then 8-12 weekly

Side Effects: Diarrhoea, nausea, infection, myelosuppression, hepatotoxicity, severe teratogenicity

Clinical Evidence:

Approximately 70-80% sustained response

Delayed onset (≥4 months)

Switch to Myfortic if GI side effects

1g MMF = 720mg Myfortic

Azathioprine:

Dosing: 1-2.5mg/kg daily

Essential: TPMT level pre-treatment

Safe during pregnancy

Other agents (Limited evidence):

Dapsone - One RCT showed slight steroid-sparing effect

Tetracyclines - Limited evidence, adjunctive use only

Methotrexate - Retrospective studies, weak evidence

Rituximab:

Rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) works by destroying B cells, effectively eliminating the "factories" responsible for producing the harmful autoantibodies that cause pemphigus.

Indications:

Licensed for pemphigus vulgaris

European Guidelines: Favour earlier use as first-line therapy

Consideration in UK:

Failure of MMF/Azathioprine after 3-6 months

Unacceptable prednisolone dose (>7.5mg daily)

Clinical evidence - RITUX-3 Trial (First-line use):

90 patients with PV/PF

Rituximab + short-term prednisolone (3-6 months) vs standard prednisolone (12-18 months)

Primary endpoint met: Complete remission without steroids at 24 months

Superior efficacy with fewer adverse events

Complete remission: 89% vs 34%

Relapse rates: 42% vs 83%

Standard Protocol:

1g × 2 infusions, 2 weeks apart

Licensed for additional 500mg at 12 and 18 months, then 6-monthly

St. John's Practice: Base repeat dosing on clinical/immunological picture

Pre-medication:

IV methylprednisolone 100mg

Paracetamol

Chlorphenamine

Monitoring:

B-cell counts and antibody titres

B-cell repopulation predicts clinical relapse

Contraindications:

Severe active infection

Severe heart failure

Side Effects:

Infusion reactions (headache, fever, nausea, chills)

Increased infection risk (HSV, VZV, respiratory, UTI)

Hepatitis B reactivation

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (extremely rare in AIBD)

Covid-19 considerations and vaccination Strategy:

Critical: Vaccinate 2 weeks prior to first rituximab dose

Significantly impaired vaccination response for ≥1 year post-treatment

Increased risk of severe COVID-19 infection

Consent patients regarding COVID morbidity/mortality risk

Adjuvant systemic agents considerations:

St. John’s half the MMF dose (eg 1g bd to 500mg bd) when commencing rituximab to avoid excessive immunosuppression

The dose is reduced on the first day of the infusion

ADVANCED AND RESCUE THERAPIES

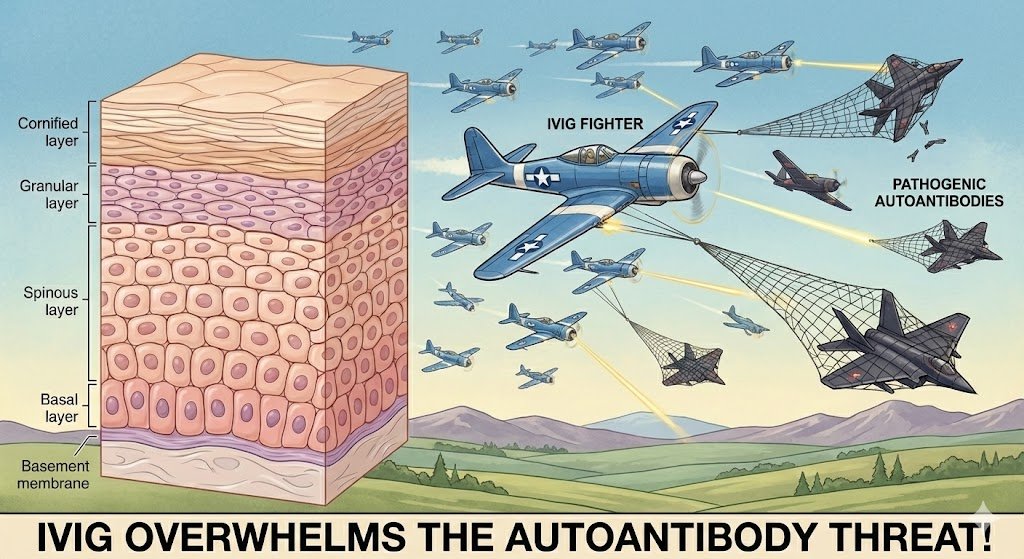

IVIG (intravenous immunoglobulin)

Mechanism:

Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) works by providing a high concentration of donor antibodies that neutralize and accelerate the clearance of the patient's own harmful autoantibodies, thereby preventing them from damaging the skin's cell-to-cell bonds.

Dosing: 2g/kg divided over 3-5 days monthly × 3 cycles

Pre-screening:

Baseline immunoglobulins (exclude IgA deficiency)

If given IVIG with IgA deficiency can develop antibodies to IgA and develop anaphylaxis

Baseline hepatitis serology

When receive IVIG can get passive transfer of antibodies - such as HBcAb, HBsAb, anti-HCV

But antigens should will remain negative - eg anti HBsAg will remain negative and HBV DNA (PCR) will remain negative

Assess thrombosis risk

Uses:

Severe acute disease (inpatient setting)

"Bridging" therapy while awaiting immunosuppression effect

Patients where immunosuppression risky (malignancy/infection)

Cyclophosphamide:

Evidence: 85% disease control in severe PV (oral 2-2.5mg/kg)

Dosing Options:

Oral: 2-2.5mg/kg daily

Pulsed IV: 500mg monthly + 3 × IV methylprednisolone 500mg

Low-dose oral: 50mg OD between pulses

Limitations: Myelosuppression, alopecia, haemorrhagic cystitis, fertility issues

Plasma Exchange:

Removes pathogenic immunoglobulins + beneficial proteins

Risk of rebound antibody production

RCT in newly diagnosed patients: no benefit demonstrated

Immunoadsorption:

Selective removal of immunoglobulins

Preserves useful plasma components

Expensive, limited access

Reserved for refractory cases

MONITORING AND FOLLOW-UP

Clinical assessment:

Control: No new lesions forming, existing lesions healing

Remission: Complete healing maintained for ≥6 months

Serological monitoring:

Desmoglein 1 and 3 ELISAs at each visit

Titres correlate with disease activity

Normalised antibodies: Much lower flare risk

Guide for treatment withdrawal

Steroid Withdrawal Protocol

Clinical remission for 6-12 months

Serological remission (normal/significantly reduced antibodies)

Gradual MMF wean first

9am cortisol before reducing prednisolone <5mg

Slow steroid taper with endocrine input if needed

Bone Protection

Baseline DEXA essential

FRAX score: Sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX

NOGG guidelines: nogg.org.uk/full-guideline

Bisphosphonates if above intervention threshold

All patients: adequate calcium and vitamin

Management pemphigus sub-types

Management of Pemphigus Foliaceus

Management follows the same treatment ladder as pemphigus vulgaris, tailored to disease severity.

As pemphigus foliaceus lacks mucosal involvement, patients are often less severely affected overall.

Topical corticosteroids may be sufficient for limited disease. For more widespread disease, oral prednisolone with a steroid-sparing agent (typically MMF) is used, with escalation to rituximab for refractory cases as needed.

Management of Paraneoplastic Pemphigus

Treatment of the underlying malignancy is essential

The prognosis is generally poor, with reported one-year mortality rates of up to 90%.

This is attributable to the aggressive mucocutaneous disease, the associated underlying neoplasm (commonly NHL, CLL, Castleman's disease, or thymoma), and the potential for developing bronchiolitis obliterans.

Immunosuppressive therapy follows similar principles to pemphigus vulgaris, but responses are often limited if the underlying malignancy cannot be controlled.

DEEP BLISTERING

If the split occurs in the basement membranze zone the blisters will be more tense

The basement membrane zone is complex with multiple proteins within it

Different clinical conditions occurs due to lack of specific proteins through attack or congenital lack of these proteins (epidermolysis bullosa congenita)

BULLOUS PEMPHIGOID

Introduction

The most common immune blistering disease

Due to antibodies (predominantly IgG) binding to targets in within the DEJ

BP 180 (aka BP Ag 2/Collagen XVII) - commoner

BP. 230 (aka BP Ag1)

This leads to the formation of sub-epidermal bullae

Epidemiology

Predominantly a disease of the elderly

Can affect any age and paediatric cases have been reported

Genetics:

There may be a genetic tendency towards the disease and there have been a few HLA associations identified (DR-B1, DQ-A1, DQ-B1)

Drugs:

Dipeptidyl-4 drugs (aka DPP-4 or gliptins) are associated with a x 3 fold increase in developing the disease

Other potential triggers - loop diuretics, thiazide diuretics, aldosterone antagonists

Neurological disease:

Patients with bullous pemphigoid (BP) have a recognised increased prevalence of neurological disease.

Dementia

Multiple sclerosis

Parkinson’s disease

Stroke

Epilepsy

This association is supported by the presence of neural isoforms of BP230 in both the central and peripheral nervous systems.

Clincial presentation

Pre-bullous phase of BP:

Often get a prodromal phase which can occur for weeks or months before the onset of blistering

Usually characterised by urticated erythema (lesion appear like hives)

Patients can just have a generalised pruritius so in pruritic elderly patients without a rash you can consider indirect immunoflourescence for BP 180/230 if no other cause is found

Bullous phase of BP:

Patients then develop tense fluid-filled bullae on normal skin or erythematous base

Fluid tends to be serous or can be haemorrhagic

Bullae can be widespread, mainly on trunk and limbs

Blisters can be intensely itchy

Bullae rupture to leave erosions which heal without scarring (although there may be persistent erythema)

Milia formation is rare which differentiates it from other sub-epidermal diseases

Oral BP:

Affects mucosal surfaces in only 10% of patients

Tend to be shorter in duration than MMP and non-scarring so if they are persistent and difficult to treat consider MMP

Investigations

Dermnet - https://dermnetnz.org/topics/bullous-pemphigoid-pathologyDdx: Sub-epidermal split with eosinophils:

Bullous pemphigoid

Bullous drug eruption

Bullous arthropod bite

Prognostic factors in bullous pemphigoid:

Treatment can be tricky as patients usually elderly (mean age 80)

Often have poor general health

Deletrious prognostic factors:

Older age

Cardiac insufficiency

Dementia

Past history of stroke

Poor general condition

Use of high doses of corticosteroids

Management

There are currently two major sets of guidelines regarding the management of bullous pemphigoid (BP):

• Venning VA, et al. British Association of Dermatologists' (BAD) guidelines for the management of bullous pemphigoid 2012. Br J Dermatol.

• Borradori L, et al. Updated S2K guidelines for the management of bullous pemphigoid initiated by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV). 2022. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol.

One key difference between these documents lies in the approach to systemic corticosteroid dosing

The 2012 BAD guidelines historically recommended a stratified approach to oral prednisolone based on disease severity, suggesting 0.75–1.0 mg/kg for severe cases, 0.5 mg/kg for moderate disease, and 0.3 mg/kg for mild or localised cases3. However, the 2022 European (EADV) guidelines now recommend a standard starting dose of 0.5 mg/kg/day across all severity levels (mild, moderate, and severe)45.

This shift is based on evidence that high-dose regimens (1.0 mg/kg) are associated with significantly higher mortality and treatment-related complications in the elderly population typically affected by BP. Current practice at St. John’s Institute of Dermatology—whose experts contributed to the 2022 European update—aligns with this safer, moderate-dose starting point

As with pemphigus management I will discuss the general approach that was taken in St. John’s although practices may differ elsewhere

General measures

General skin care principles:

Antibacterial soap substitutes: Octenisan wash once daily (lather all over, leave for 5 minutes, wash off, pat dry)

Emollient: Emulsifying ointment or something similar

Non-adherent dressings: Mepitel/Mepilex as appropriate

Potassium permanganate soaks: Helpful for wet, weepy erosions that need drying out

Blister management:

Gently cleanse blister with antimicrobial solution, taking care not to rupture

Pierce blister at base with sterile needle/syringe (bevel facing up)

Select a site where fluid will drain by gravity to discourage refilling

Gently apply pressure with sterile gauze to facilitate drainage

DO NOT DE-ROOF THE BLISTER!

After drainage, cleanse again with antimicrobial solution

First line agents

Can consider topical steroids and doxycycline 200mg daily in certain cases if on the milder spectrum and patient has many co-morbidities and is at higher risk from systemic steroid complications

Many patient however will require oral steroids to induce remission and some will require second line immunosuppressive agent or dapsone

Topical steroids:

Dermovate (clobetasol propionate) ointment to eroded and erythematous areas on body

Eumovate ointment to affected areas on the face

Tetracycline antibiotics:

Doxycyline 200mg daily (eg 100mg bd)

Used in bullous pemphigoid for their anti-inflammatory effects (not anti-microbial)

Many clinicians commence doxycycline alongside topical or oral prednisolone as an adjunct

Stomach protection is important especially if considering systemic steroids as both drugs can cause gastritis/oesophagitis

Evidence for use of doxycycline in bullous pemphigoid is noted below

BLISTER Trial Evidence (2017 UK RCT)

Compared doxycycline 200mg daily vs prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg in 121 patients

At 6 weeks: Prednisolone more effective for short-term blister control (91% vs 74% achieving ≤3 blisters)

BUT doxycycline met non-inferiority margin and had better safety profile

Conclusion (from study): Doxycycline is a reasonable first-line option, especially when minimising corticosteroid exposure is important

Oral steroids:

The aim is to try to start at the lowest possible dose that might control the disease

Caution to be applied in patients with diabetes, hypertension or poor bone health

In patients with moderate to severe disease reasonable to start at 0.5mg/kg

Maintain this till have control of disease activity - defined as where no new lesions are forming and existing lesions are beginning to heal

Then begin to wean

Second line agents

Consider adding a second line agent if the disease starts to flare on the reduction of prednisolone

Mycophenolate mofetil:

In general prepared to azathioprine due to risk of skin cancer associated with long term azathioprine use

Dosing: Start 500mg bd and increase to 1g bd within a couple of weeks

Max dose: 2g daily (3g not superior and associated with more side effects)

Side effedcts: GI disturbance (dose-dependenant, up to 20% ag 2g daily)

Myfortic (mycophenolic acid) is an alternative if have GI side effects with MMF

Contraindicated in pregnancy (severe teratogenicity)

Azathioprine:

Roughly equivalent clinical efficacy to MMF

TPMT check essential before starting

Key concern: Increased risk of skin cancer (SCC) with long-term use

Considered safe during pregnancy

Methotrexate:

Generally evidence base less than MMF/Azathioprine

If used, consider using a lower dose (5-12.5mg weekly subcut) due to the increased risk of complications in an elderly population

Dapsone:

Can be considered in patients who have contraindications to oral steroids and other immunosuppressive treatments in mild to moderate bullous pemphigoid

Be careful prescribing dapsone in older patients with cardiovascular disease (as they would be more sensitive to any anaemia that could occur with dapsone)

Check G6PD before starting

Side effects: Haemolytic anaemia, nausea, headache, methaemoglobinaemia, peripheral neuropathy (predominantly motor)

Rituximab:

Data suggests it is not as rapidly or completely effective for pemphigoid as it is for pemphigus

But can be considered in refractory pemphigoid

IVIG:

Can be very helpful in an acute setting – eg hospitalised patients

• 2g/kg monthly typically split over 3-5 days

• +/- methyl prednisolone 250–500mg daily ×3 (to help speed up response)

• Repeat for at least 3 cycles

Cyclophosphamide:

Generally would be more likely to try rituximab first prior to cyclophosphamide

Dupilumab:

LIBERTY-BP ADEPT Trial (Phase 2/3 RCT, n=106)

Press release - not fully published yet

First positive RCT for a biologic in BP

Sustained remission at week 36: 20% vs 4% placebo (both arms received tapering steroids)

Significant steroid-sparing effects noted

Safety comparable to placebo; conjunctivitis more common with dupilumab

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38443648/

Murrell DF et al. Study Design of a Phase 2/3 Randomized Controlled Trial of Dupilumab in Adults with Bullous Pemphigoid: LIBERTY-BP ADEPT. Adv Ther. 2024;41(7):2991-3002.Retrospective Cohort Study (n=103, 34 hospitals in Spain)

53% complete response by week 4; 96% clear by week 52

80% reduction in corticosteroid use

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39418120/

Melgosa Ramos FJ, et al. Real-world evaluation of the effectiveness and safety of dupilumab in bullous pemphigoid: an ambispective multicentre case series. Br J Dermatol. 2025.Impression -

Dupilumab has RCT-level evidence demonstrating efficacy in BP with rapid real-world responses.

Omalizumab:

French Observational Multicentre Study (n=100)

All patients refractory to ≥1 treatment line

Complete remission ahieved in 77%

Median time to complete remission: 3 months.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37792727/

Chebani R, Lombart F, Chaby G, et al. Omalizumab in the treatment of bullous pemphigoid resistant to first-line therapy: a French national multicentre retrospective study of 100 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2024;190(2):258-265.Systematic Review (n=56)

Overall response: 87.5% (55% CR, 32% PR)

57% relapsed on discontinuation but most recaptured response

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35379011/

D'Aguanno et al. Omalizumab for the Treatment of Bullous Pemphigoid: A Systematic Review of Efficacy and Safety. J Cutan Med Surg. 2022;MUCOUS MEMBRANE PEMPHIGOID

Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) is a mucocutaneous blistering disease characterised by antibodies against components of the dermo-epidermal junction (DEJ) with predominant mucosal involvement.

It is much rarer than bullous pemphigoid

Incidence: approximately 2 per million per year

Mean age of onset: 60-65 years

Female preponderance: 1.5-2.3:1

Can affect multiple mucosal sites with potential for scarring

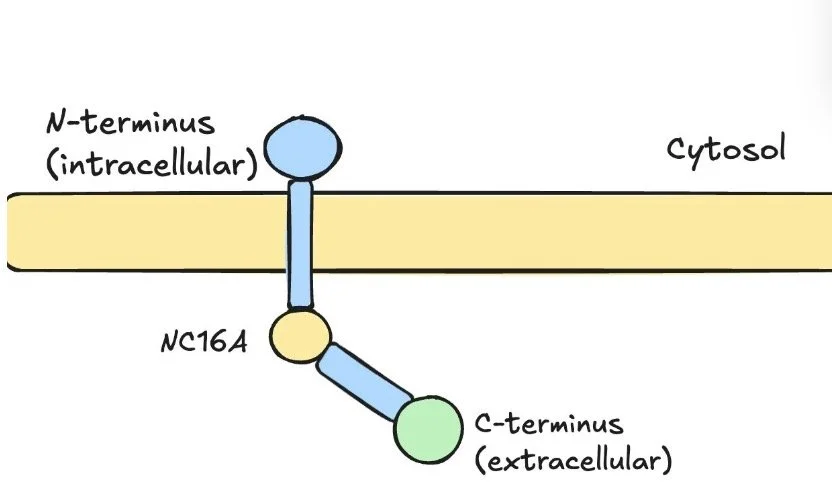

MMP is mediated by autoantibodies targeting multiple basement membrane zone antigens.

Unlike bullous pemphigoid where the NC16A domain of BP180 is predominantly targeted, MMP often involves antibodies to the C-terminal domain of BP180

Standard ELISAs miss the C-terminal domain so might not come up positive in MMP

Clinical presentation

Oral involvement (85%)

Usually the presenting feature and frequently are the most challenging to manage

Shallow blisters/erosion palate

Desqaumative gingivitis

Dermnet - https://dermnetnz.org/topics/mucous-membrane-pemphigoid

Most common intraoral sites:

Gingiva (80%)- commonest and often presents as a desquamative gingivitis

Buccal mucosa (approx 60%)

Palate (25%)

Alveolar ridge (15%)

Tongue (15%)

Tend to get a chronic erosive gingivitis wiht painful ulceration

Intact blisters are rarely seen

Lesions heal with scarring (unlike in oral BP)

Ocular involvement (65%):

Ocular involvement requires aggressive treatment due to potential for blindness

Adhesions between bulbar mucosa and conjunctiva

Clincial progression:

Early: Conjunctival erythema, irritation, foreign body sensation, mucous discharge

Intermediate: Shortening of inferior fornix, symblepharon formation (adhesions between conjunctival surfaces)

Late: Trichiasis (eyelashes pointing in), entropion (inward angulation of eyelid), lagophthalmos (abnormal eye closure)

End-stage: Corneal scarring leading to blindness

Clinical pearl: β4 integrin antibodies are particularly associated with ocular lesions.

Anogenital invovlement (20%)

Erosions and scarring can mimic lichen sclerosus

Results in architectural abnormalities

Vaginal stenosis may occur in women

Laryngeal/Pharyngeal/Oesophageal Involvement (10-20%)

Voice hoarseness (laryngeal involvement)

Odynophagia

Patients with hoarse voice need urgent ENT review

Cutaneous Involvement (25-30%)

Lesions resemble bullous pemphigoid

Tense bullae on normal or erythematous skin

Heal with scarring and milia formation (unlike BP)

Scalp involvement can cause scarring alopecia

Laminin 332 MMP:

Associated with severe MMP phenotype

25-30% association with solid organ malignancy

All patients with base-binding pattern on salt-split skin should have CT chest/abdomen/pelvis

Can’t test for laminin-332 with ELISA in Ireland/UK

Investigations

H&E:

Subepidermal blister with mixed inflammatory infiltrate (similar to BP)

But often can be a ‘cell-poor’ blister

Tends to have fewer eosinophils than bullous pemphigoid

See fibrosis and scarring in later stages

Histology alone cannot distinguish MMP from BP, EBA or Linear IgA disease

DIF:

Linear deposition of IgG, IgA and/orC3 at BMZ

IgA deposition more prevalent in MMP than BP

IIF:

Interestingly, IIF can be is lower yield for MMP compared to Bullous Pemphigoid so you are more likely to have a negative test

Salt split skin testing:

In MMP antibodies can bind to the roof or the floor

If binds to the floor you might think that laminin-332 is being targeted so consider ordering a CT chest/abdo/pelvis (? underlying malignancy)

ELISA:

Some labs may be able to test for anti-BP 180 carboxy terminal domain and anti-laminin-332

Management

MMP is generally more challenging to treat than bullous pemphigoid. It typically follows a chronic relapsing course, and complete remission is less common than in BP. The presence of dual IgG and IgA antibodies at the DEJ is a poor prognostic indicator.

First Line

Topical corticosteroids (superpotent to affected areas)

Corticosteroid mouthwashes (betamethasone 500mcg dissolved in water, or fluticasone nasules)

Tetracycline antibiotics (doxycycline 200mg daily)

Dapsone

Second Line

Oral prednisolone (0.3–0.5mg/kg) combined with:

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) or azathioprine

Continue dapsone as adjunctive therapy

Third Line

Rituximab (1g × 2, two weeks apart)

Cyclophosphamide

IVIG (2g/kg over 3–5 days)

Ocular involvement requires aggressive treatment — collaborate closely with ophthalmology

MMP often requires combination therapy (e.g., prednisolone + dapsone + immunosuppression) to achieve disease control

Dapsone plays a role in the management of MMP due to the role of neutrophils in the subepidermal blistering

Cicatricial pemphigoid:

Used to be used interchangeably with MMP

Ideally should only be used for rare events where you have pemphigoid that causes scarring but does not affect mucous membranes (but in practice cicatricial pemphigoid and MMP are probably still used interchangably)

Need to exclude other sub-epidermal blistering conditions (EBA, MMP) prior to making diagnosis of cicatricial pemphigoid

Brunsting-Perry cicatricial pemphigoid:

Is a sub-type of pemphigoid presenting as blisters, erosions and crust on the head and neck

These tend to heal with scarring

Antibodies targeted include BP-180, BP-230 and to a lesser extent Collagen VII and laminin-332

PEMPHIGOID GESTATIONIS

Blistering disorder that can occur during pregnancy

Postulated that HLA mismatch between mother and foetus may trigger an immune response that cross-reacts with maternal skin

Characterised by IgG antibodies directed against BP 180 in the BMZ

Antibodies to BP230 can be present in about 10%, the significance is unclear

Clinical features:

Usually presents in a prebullous phase involving urticarial plaques and papules on the abdomen that characteristially involve the periumbilical skin (may start here)

The rash may then spread to the rest of the torso, the intertriginous areas and extremities

The face, palms and soles usually spared

Mucosal involvement occurs in less than 20% of cases

Dermnet - https://dermnetnz.org/topics/pemphigoid-gestationisDermnet - https://dermnetnz.org/topics/pemphigoid-gestationisCan occur any time between 4 weeks gestation and 5 weeks postpartum with the majority presenting in the 2nd and 3rd trimester

Onset in 1st or 2nd trimester can lead to adverse pregnancy outcomes:

Decreased gestational age at delivery

Preterm birth

Low birth weight

But overall it has a generally good foteal prognosis

Can be associated with other autoimmune diseases in the mother (eg Grave’s disease) and more rarely with trophoblastic tumours (choriocarcinoma, hydatidiform moles)

H&E:

Identical to bullous pemphigoid

DIF:

Linear C3 in all cases, IgG only seen in approx 25% of cases

ELISA:

Antibodies to NC16a domain of BP 180 seen(very sensitive and specific)

Management

Case reports and small case series have suggested Dupilumab could also be effective in the management of pemphigoid gestationis

LINEAR IgA DISEASE

Linear IgA bullouse dermatosis (LABD) is a sub-epidermal blistering disease characterised by linear deposition of IgA at BMZ

It is the commonest autoimmune blistering condition in children

Epidemiology:

Bimodal age distribution:

Childhood: peak at approximately 5 years (chronic bullous disease of childhood)

Adult: peak at 60-65 years

Slight female preponderance

Can be idiopathic or drug-induced

Drug induced:

Vancomycin - most commonly implicated

NSAIDs

Penicillins and other antibiotics

Diclofenac

Lithium

Captopril

Target antigens:

LAD-1 - This is the most frequently identified target and represents the cleaved extracellular portion of BP180

Other antigens that can be targeted - BP 180, BP 230, Type VII Colalgen, Laminin-332

Clinical pearl:

Most patients have both IgA and IgG antibodies and there can be a significant overlap between BP and LABD.

The key distinguishing feature is that IgA flourescence intensity is higher than IgG and C3 on DIF

Clinical presentation

Skin:

Tense blisters, urticated plaques, and erosions

"String of pearls" or "cluster of jewels" sign: annular lesions with peripheral bullae arranged in a rosette pattern (pathognomonic)

Distribution: trunk, limbs, face

Lesions heal WITHOUT scarring

String of pearls sign

https://dermnetnz.org/topics/linear-iga-bullous-disease

Childhood LABD (‘Chronic bullous disease of childhood’)

Perioral and perineal distribution characteristic

Also affects trunk and limbs

Annular configuration with "cluster of jewels" pattern often prominent

Lesions may be very itchy

Mucosal Involvement:

Occurs in up to 70% of patients

Oral mucosa: erosions, can overlap with MMP

Tongue involvement may be prominent (especially IgA-predominant MMP)

Ocular, nasal, pharyngeal, laryngeal involvement possible

May scar at mucosal sites (overlap with MMP)

Investigations

H&E:

Sub-epidermal blister

Inflammatory infiltrate with numerous NEUTROPHILS

Neutrophils arranged at dermal papillae (papillary microabscesses)

May be indistinguishable from DH or BP histologically

Ddx sub-epidermal split with many neutrophils:

Linear IgA

Bullous Lupus

Dermatitis herpetiformis

(still need to consider BP in any sub-epidermal split regardless of infiltrate)

DIF:

LINEAR IgA deposition at the basement membrane zone (defining feature)

May also have IgG and C3, but IgA intensity is HIGHER

This contrasts with pemphigoid where IgG/C3 predominate

Salt-Split Skin:

Can localise to the roof or floor depending on the target antigen

Roof (epidermal side): LAD-1, BP180 targets

Floor (dermal side): type VII collagen, laminin-332 targets

ELISA:

May be positive for BP 180, BP 230 or Type VII Collagen

There is no commercially available ELISA in UK/Ireland for LAD-1

Management:

Linear IgA disease can be very responsive to Dapsone and you can often see dramatic responses to 48-72 hours of Dapsone treatment

Prognosis:

Good prognosis overall

Most children go into remission within 2 years

Drug-induced LABD resolves about 4-8 weeks after stopping the culprit drug

Adult idiopathic disease may be more persistent

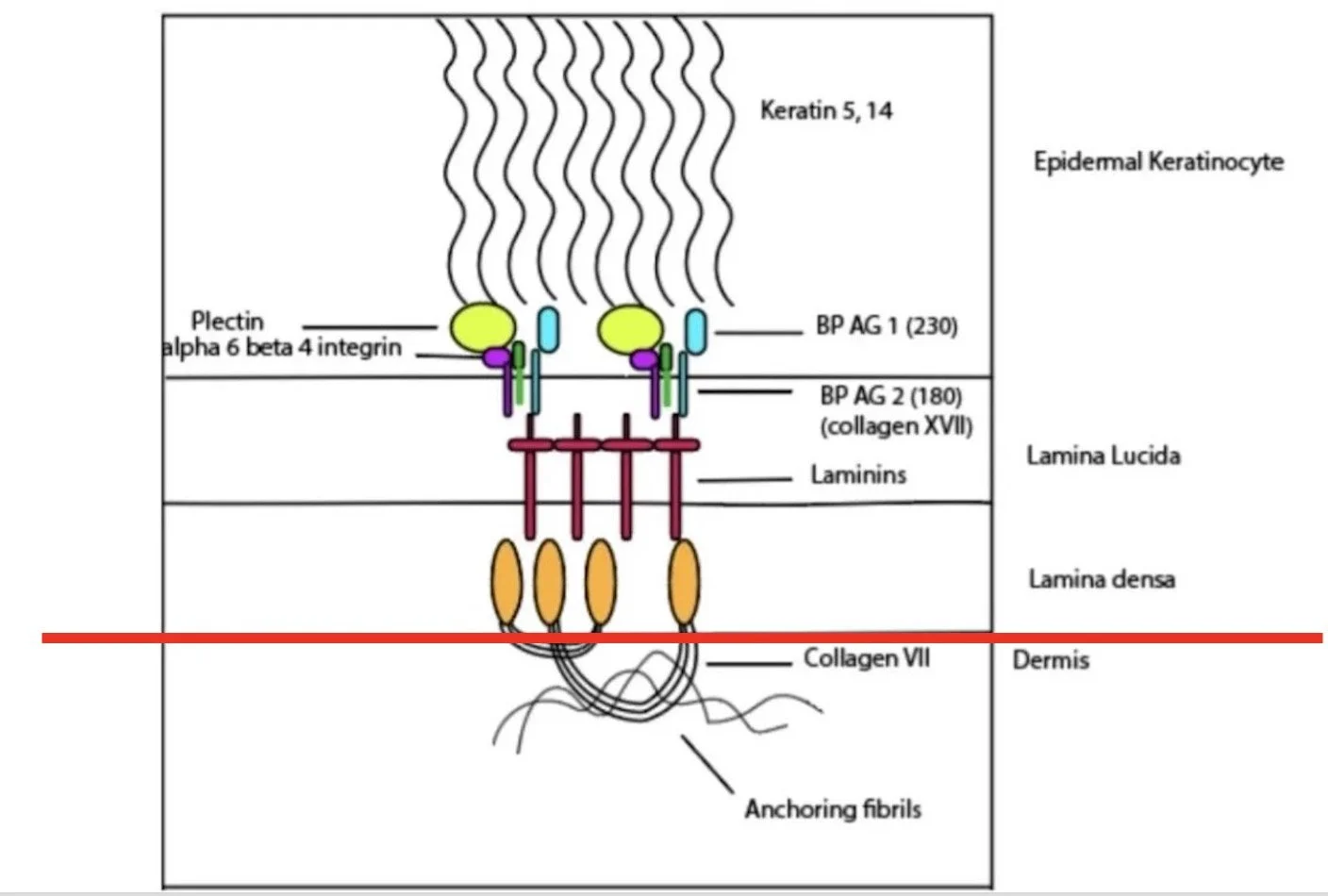

EPIDERMOLYSIS BULLOSA ACQUISITA

EBA is a rare, acquired autoimmune sub-epidermal blistering disease caused by IgG autoantibodies to type VII collagen, the main component of anchoring fibrils at the dermal–epidermal junction.

Key points

Onset: 45–55 years

Sex: M = F

Incidence: ~0.2–0.5 per million/year

Associated with inflammatory bowel disease, especially Crohn’s disease

Clincial features

Two main phenotypes (may coexist)

Mechanobullous (classical) variant:

Trauma-induced tense blisters

Dorsal hands, elbows, knees, feet

Healing with scarring and milia (hallmark)

Nail dystrophy or loss

Inflammatory (BP-like) variant:

Widespread tense bullae on erythematous skin

Mimics BP, LABD, or MMP

Scarring less prominent initially

Mucosal disease (common, often severe)

Oral ulcers → scarring, ankyloglossia, microstomia

Oesophageal strictures, dysphagia

Ocular conjunctival scarring

Laryngeal, anogenital involvement

Oral clues

Deep sub-epidermal ulcers

Tongue scarring

Relative gingival sparing (vs MMP)

Investigations

H&E

Sub-epdermal blisters +/- neutrophils seen

Can be ‘cell poor’ with minimal inflammatory infiltrate

DIF:

Linear IgG +/- C3 seen at BMZ

Salt-split skin:

Binds to the floor

Serration pattern:

U-serrated

ELISA:

Type VII collagen

Management

Due to the rarity of the disease can be difficult to know which are the most effective medications for this condition

Mechanobullous variant tends to be quite resistant to standard immunosuppressive medicataions

EBA is often treatment-resistant and usually requires combination therapy.

General care

Minimise trauma

Wound care, infection prevention

Nutritional support if oral disease

Screen for IBD

Treatment considerations:

Topical steroids

Colchicine

Dapsone

Oral corticosteroids

MMF

Refractory disease:

Rituximab

IVIG

Immunoadsorption

Key agents

Colchicine: 500 mcg BD (mechanobullous disease)

Dapsone: useful due to neutrophilic pathology

Prednisolone: ~0.5 mg/kg (usually with steroid-sparing agent)

MMF: preferred steroid-sparing option

Rituximab: refractory disease (slower response than pemphigus)

IVIG: severe disease or contraindication to immunosuppression

Mucosal disease

Treat aggressively

Early ophthalmology, ENT, and GI involvement essential

There are many inherited forms of epidermolysis bullosa

This type is an acquired mechanobullous disorder

Get antibodies to type collagen 7 which constitutes part of the anchoring fibrils which attach the basement membrane to the underlying dermis

Clinical:

Get non-inflammatory tense blisters occur at sites of trauma/friction (hands, wrists, ankles, knees) Can get mucous membrane involvement also

As, split is below the lamina densa it scars with scarring milia and atrophic scarring

May get some mucous membrane invovlement and in some cases can get oesophageal stenosis

H&E:

Sub-epidermal blistering

‘Often cell poor’ (minimal inflammation)

Ddx cell poor sub-epidermal blister:

EBA

PCT

(consiser BP as it is so common)

DIF:

Linear IgG +/- C3 +/- IgA in Basement membrane

Another method that may help differentiate EBA from the pemphigoid diseases is the serration pattern

This involves looking at the linear flourescence and if the overall pattern looks like:

A repeating ‘u’: think Epidermolysis bullosa acquisita or bullous SLE

A repeating ‘n’: think of the other pemphigoid diseases -BP, MMP, anti-p200 pemphigoid, linear IgA dermatosis

IIF with salt split skin test:

Antibodies tend to attach to the dermal side

ELISA:

Positive antibodies against Collagen VII

BULLOUS LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS (BSLE)

BSLE results from autoantibodies targeting BMZ antigens, most often type VII collagen

Epidemiology:

Affects < 5% of SLE patients

Strong female predominance (approx 9:1)

Typical onset 20-40 years

More common in patients of African descent

May precede or complicate established SLE

Target antigens:

Type VII Collagen is the most common

BP 180, BP 230, Laminin-332 can also be affected

Clinical features:

Cutaneous:

Widespread tense vesicles and bullae

On erythematous or normal skin

Often sun-exposed areas (face, neck, trunk, arms)

Interestingly despite collagen VII being targeted lesions usually heal without scarring or milia (in contrast to EBA)

May coexist with cutaneous lupus features

https://dermnetnz.org/topics/bullous-systemic-lupus-erythematosusMucosa:

Oral involvement in up to 50%

May affect pharynx, oesophagus, conjunctiva

Typically heals without scarring

Investigations

Lab investigations to include:

FBC, U&E, LFT

ANA

Anti-dsDNA - often positive

Low complement levels may be seen

ENA/antiphospholipids antibodies if indicated

H&E:

Sub-epidermal blister

Prominent neutrophilic infiltrate

May see neutrophilic microabscesses at dermal papillae

May see mucin within the dermis

DIF:

Linear or granular IgG/IgM/IgA/C3 at the DEJ

Salt split skin:

Binds to the floor

Serration:

u-serrated pattern

ELISA:

Type VII collagen usally positive

Management

Supportive care:

Sun protection advice

Treat underlying SLE activity as would normally do

First-line:

Dapsone 25–150 mg daily (start low, titrate)

Rapid response (days–weeks)

Second line:

Systemic corticosteroids

Hydroxychloroquine

MMF

Azathioprine

Rituximab

Prognosis:

Transient in the majority of cases and usually regresses with no further flares, irrespective of the activity of the systemic disease.

Typically resolves without milia or scarring but can leave hypo- or hyper-pigmentation.

DERMATITIS HERPETIFORMIS

Dermatitis herpetiformis is an IgA-mediated sub-epidermal blistering disease and represents the cutaneous manifestation of coeliac disease.

It is defined by granular IgA deposition in the dermal papillae.

Key points

Predominantly affects people of Northern European descent

Typical onset: 30–40 years (can occur at any age)

Male predominance (≈2:1)

Incidence: ~1–10 per 100,000/year

Association with coeliac disease

All patients have gluten-sensitive enteropathy on biopsy

Only 10–20% have overt GI symptoms

Severity of skin disease does not correlate with gut involvement

Conversely, around 15-25% of Coeliac patients will have DH

Clinical pearl:

Diagnosis of DH mandates coeliac work-up and lifelong management due to lymphoma risk.

Pathogenesis:

DH results from a gluten-driven IgA immune response with cross-reactivity between gut and skin transglutaminases.

Target antigens:

Tissue transglutaminase (TG2) – gut (coeliac disease)

Epidermal transglutaminase (TG3) – skin

Mechanism

Gluten exposure in genetically susceptible individuals

IgA antibodies to TG2 form in the gut

Cross-reactive IgA to TG3 develops

IgA–TG3 complexes deposit in dermal papillae

Neutrophil recruitment → protease release

Sub-epidermal blister formation

Clinical features

Skin:

Intensely pruritic papules, vesicles, and erosions

Vesicles often absent due to scratching

Grouped (“herpetiform”) and symmetrical distribution

Clinical pearl: Patients usually present with excoriations and not blisters

Classic sites:

Extensor elbows and knees

Buttocks (highly characteristic)

Scalp, scapulae, sacrum

https://dermnetnz.org/topics/dermatitis-herpetiformis

Systemic associations:

GI symptoms uncommon

Iron deficiiency anaaemia

Associated autoimmune disease - thyroid disease, T1DM, Pernicious anaemia

Investigations

H&E:

The most characteristic findings occur at the tips of the dermal papilla

Neutrophilic microbascesses

May see some eosinophils also

‘Shaggy fibrin deposition’

As inflammation progresses you get dermal papillary oedema and sub-epidermal blistering

DIF:

Granular IgA in dermal papillae +/- C3

Serology:

IgA anti-tTG: positive in >90%

IgA anti-endomysial antigen: highly specific

IgA anti-TG3: more specific for DH (research/specialist labs only)

Note: Standard lab tTG assays measure tTG2 (gut) only, not tTG3 – but tTG2 is sufficient for clinical screening.

Check total IgA – ~2% are IgA deficient → use IgG-based tests (tTG-IgG, DGP-IgG)

Gluten-free diet pitfall:

Serology normalises within 6–12 months on a GFD. If already gluten-free:

DIF remains positive longest (months–years) → most reliable test

Gluten challenge: 6–8 weeks before repeating serology (often poorly tolerated)

Always request serology before dietary modification where possible.

Systemic Workup:

FBC, Iron, B12, Folate, TFT

Gastroenterology referral should be considered

Villous biopsy - will show villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia

Management

Strict lifelong gluten-free diet (GFD)

Treats both skin and gut disease

Reduces lymphoma risk

Skin improvement takes months–years

Dapsone (rapid symptomatic control)

25–50 mg daily → up to 100–200 mg

Dramatic response usually seen within days

If they fail to respond to dapsone reconsider the diagnosis

Alternatives:

Sulfapyridine

Sulfasalizine

Long-term prognosis:

Many patients can discontinue dapsone with strict gluten free diet

Monitor coeliac serology for compliance

Prognosis:

Excellent with adherence to GFD

Increased lymphoma risk with poor dietary compliance

Linear IgA disease

Question 1

Metabolic:

Porphyrias:

Metabolic disorders caused by altered activity of enzymes in the heme biosynthesis pathway

Porphyria can be subdivided into 3 main groups based upon clinical presentation:

Acute intermittent (hepatic) porphyrias - neurological symptoms

Cutaneous porphyria

Acute and cutaneous - neurologic and cutaneous symptoms

Acute hepatic: Acute intermittent porphyria

Acute and cutaneous: Hereditary coproporphyria, variegate porphyria

Cutaneous: PCT, CEP, EPP, Hepatoerytrhopoietic porphyria

Three ways in which porphyrias present in the skin:

Immediate painful photosensitivity:

Erytrhopoeitic porphyria

Mutilating photosensitivity

Congenital erythropoeitic porphyria (Gunter’s disease)

Other rare severe homozyghous porphyrias

Bullous porphyrias - skin fragility and bullae

Porphyria cutanea tarda

Variegate porphyria

What causes Porphyria?

Note:

Linear tetrapyroll also referred to as hydroxymethylbilline

Uroporphyrinogen-1synthase aka porphobilinogen deaminase (PBG-D) or hydromxymehtylbilane synthase

Haem is found in haemoglobin, myoglobin and other haem protens such as cytochromes

Haem is made from the precursors glycine and succinyl CoA

These are converted to haem by 8 chemical reaction steps

Each step is catalysed by a specific enzyme

If one enzyme has reduced activity and is not working properly you will get an acculumation particularly of the biochemical on which the enzyme works

If the biochemical is a porphyrin as in the case of some of the intermediaes above then porphyrins accumulates

Acute porphyrias occur due to direct cytotoxic effect of ALA and PBG on neural tissue

Cutaneous porphyrias due to toxic metabolites poteniated by sunlight (UV causes free radical formation)

AIP: PBG deaminase (aka uroporphyrinogen 1-synthase)

CEP: UPC

PCT: UROD

HC: Coproporhyringoen

VP: PPO

EPP: Feroocheletase

Mechanism of action

Porphyrins can be phototoxic

A photon of visible violet light (approx 408-410nm) is absorbed by porphyrin

This causes the porphyrin to be in an excited state (called a ‘triplet state’)

This can then react with oxygen and turn oxygen into its activated state (‘singlet oxygen’)

The singlet oxygen then directly damages local tissues

So think of porphyrins as little machines that convert visible light photons into tissue damage via singlet oxygen

As mentioned previously porphyrias can present differently in skin eg,

EPP causes an immediate, painful photosensitivity

PCT causes fragility and bullae particularly on back of hands

One hypothesis is this difference is due to the solubility of the different porphyrins due to the number of carboxylate groups (COOH) each porphyrin has which alters the solubility of the porphyrin

Uroporphyrin is water soluble

Protoporphyrin lipid soluble (and not water soluble)

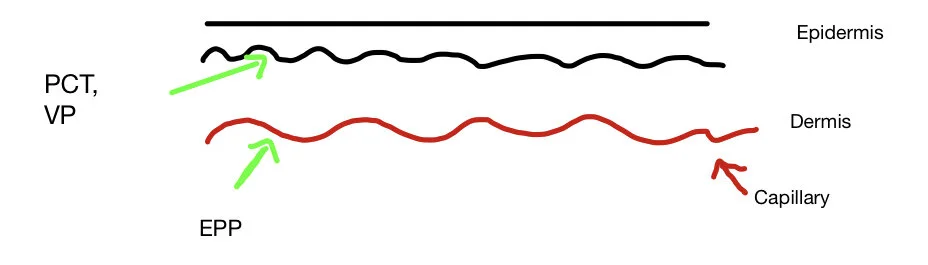

In PCT, uroporphyrin accumulates in the skin and as it is water soluble it can diffuse up to upper dermis

It is then activated by light and the phototoxic reaction occur in the upper dermis causing a split with blistering

In EPP, the protoporphyrin accumulates in the red cells and does not diffuse further than the endothelial lining of small blood vessels.

Light produces endothelial necrosis in the upper dermis causing typical pain and oedema

Porphyria cutanea tarda

PCT is the commonest of the porphyrias

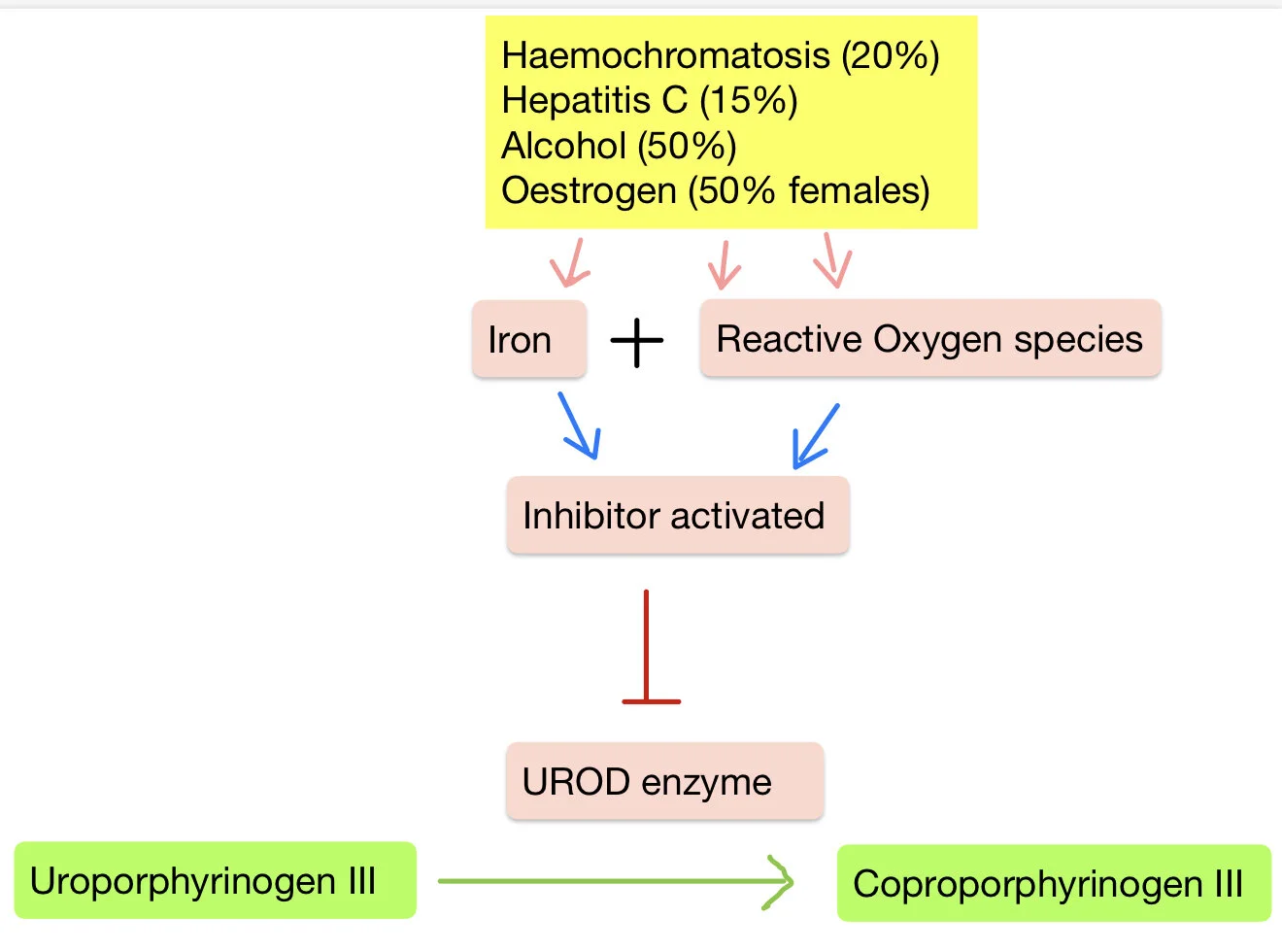

Due to an acquired or inherited deficiency in the activity of the hepatic enzyme uroporphrinogen decarboxylase which usually converts uroporphyringoen III into Coproporphyrinogen III

Decrease in activity of this liver enzyme can be multifactorial

It is due to an inhibitor UROD called uroporphomethene

This is produced particularly in the presence of an oxidising environement and increased iron in the liver

Certain conditions predispose to an environment in which this inhibitor is produced leading to PCT:

Haemochromatosis (20%)

Hepatitis C (15%)

Alcohol (50%)

Oestrogen: eg HRT (50% females)

Smoking

So in summary, inhibition of UROD leads to a build up of uroporphyrinogen III

Genetic factors may be present:

A UROD mutation which is seen in 25% of patients makes the enzyme not as effective

Therefore it requires less inhibitor activation to produce the disease so often get the disease at an earlier stage

Reduced activity of UROD leads to accumulation of porphyrins (eg uroporphyrin) which can be transported to the skin.

These porphyrins are ‘photosensitizing’

-Sunlight (UVA and visible light ranges) cause them to become excited and damage surrounding tissue.

Clinical:

Sun sensitivity

Increasingly fragile skin on back of hands and forearms

Get multiple erosions and blisters

This heals with scarring in the form of milia (tiny cysts)

Can also get hyperpigmentation on face and neck and hypertrichosis (excess hair)

Diagnosis:

Skin biopsy: sub epidermal blistering

All porphyrias that cause skin lesions have elevated plasma porphyrins

Elevated urinary uroporphyrin (and others) and fecal porphyrins indicate PCT

[Should probably do iron studies, HIV and viral hepatitis testing in these patients]

(Urine may look reddish/‘tea’ coloured)

Avoid unnecessary exposure to strong light

Pseudoporphyria

Looks like porphyria cutanea tarda

BUT porphyrin levels are normal

Reaction here is to UV light and not visible light like PCT

Symptoms:

Photosenstivity and fragility

Tense blisters at minor trauma sites (and erosions/scabs)

Often on hands and feet

Heal with scars and milia

Usually medications: (medications react with sunlight to cause photoxic reaction in skin)

· NSAIDs

· Antibiotics-doxycycline

· Diuretics- thiazides, furosemide, bumetanide

· Retinoids- acitretin, isotretinoin

· OCP

Investigations:

Phototesting to confirm photoxic action of the supected agent

Skin biopsy of blister

May check porphyrins in blood, urine and faeces to rule out PCT

Management:

Withdraw offending agent (usually goes away in weeks but cn persist)

Sun protection

Variegate porphyria:

Due to protoporphyrinogen oxidase deficiency

Looks exactly like PCT in skin

Often presents earlier than PCT (teens)

Very important to diagnose as if misdiagnose can prove fatal

Variegate porphyria can cause acute, systemic internal attacks

Acute porphyria signs/symptoms:

AIP, Variegate porphyria, hereditary coproporphyria

Can present with sudden life-threatening crisis

Most patients have one or only a few attacks followed by resolution of syndrome

Attacks occur rarely in childhood with incidence increasing after puberty

Manifest by neurovisceral symptoms and autonomic sequelae

Neuro: fatigue, confusion, seizures, motor neuropathy

GI: abdominal pain, N/V, constipation

Autonomic: hypertensive urgency, fever

Hyponatraemia

(Think in someone with unexplained neurological symptoms in someone with autonomic and/or GI symptoms and hyponatreaemia)