CUTANEOUS LUPUS INTRODUCTION

Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (CLE) is not a single disease but rather an umbrella term that encompasses several distinct conditions

These various forms of cutaneous lupus can present with very different clinical appearances and courses

Each sub-type can be associated with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) to various degrees and it is important to be aware that not everyone with CLE will develop SLE

In a dermatology clinic setting, discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) and subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) are the most likely sub-types you are going to see

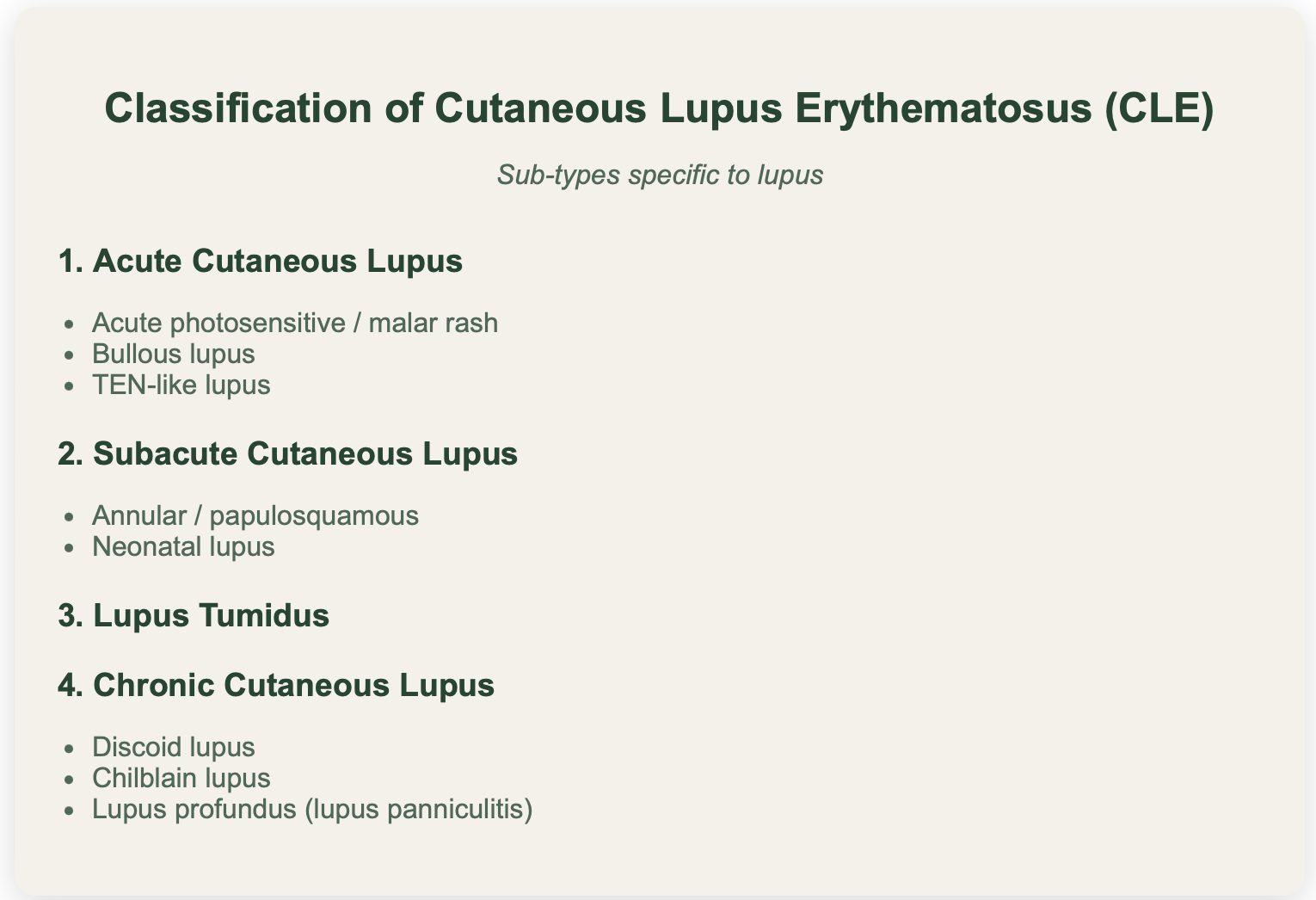

CLASSIFICATION OF CUTANEOUS LUPUS

Skin disease in lupus can be specific to lupus or non-specific (ie can be seen in other diseases)

PATHOGENESIS OF LUPUS

The pathogenesis of Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (CLE) is a complex process involving numerous cells and is not yet fully understood

However, it can be conceptualized in simplified terms to provide a better understanding of the disease

The underlying issue involves a loss of immune cell tolerance, where the body's immune system mistakenly attacks its own tissues

Certain factors may predispose people to devloping lupus:

Oestrogens likely play a role (it primarily occurs in women)

Environmental factors can play a role including - Sunlight, drugs, smoking, viruses (eg EBV can trigger and flare SLE in paediatric populations)

Genes - there are about 150 genes that have been identified that can be associated with an increased risk of lupus

Here is a simplifed version of the key steps:

Initial Trigger and Cell Death - Environmental factors cause tissue injury and cell death (eg UV radiation causes damage to keratinocytes).

In lupus prone patients, there is defective clearance of apoptotic cells and increased “NETosis" (neutrophil extracellular trap formation) which leads to increased exposure of nucleic acids and intra-cytoplasmic antigens to the immune system

Activation of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells (pDCs) - These self-antigens directly activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) via specific Toll-like receptors (TLR7/9) and leads to the release of huge amounts of Type 1 Interferon. These interferons appear to be important in lupus and create a chronic inflammatory state throughout the immune system

Activation of Conventional Dendritic Cells and T Cells -

Type I interferons mature and activate conventional dendritic cells (cDCs), which present self-antigens to naive T cells. T helper cells can then become activated

B Cell activation and Autoantibody Production -

Activated T cause B cells to activate and differentiate into plasma cells. These plasma cells then produce various autoantibodies that recognise the body's own DNA material (eg ANA, anti-dsDNA, anti-Smith and anti-Ro antibodies).

Individuals can be in a 'pre-clinical phase' where they are completely well yet producing these lupus autoantibodies, with an increasing frequency over time. Clinical disease will then occur once a certain treshold is reached.

Immune complex formation and tissue damage -

Antibodies bind to nuclear antigens forming immune complexes which can be deposited in various tissues including the skin, kidneys, joints and blood vessels. These deposited immune complexes activate the complement cascade leading to the generation of inflammatory mediators and membrane attack complexes that directly damage tissues.

Self-Perpetuating Cycle and Chronic Disease

Tissue damage releases more self-antigens, which further activate dendritic cells and sustain high interferon levels, thereby establishing a self-perpetuating cycle of immune activation, autoantibody production, and tissue damage.

Also:

In lupus can also get separate antibodies directed against specific cells (eg red cells, white cells, phospholipids) which marks them for phagocytosis and destruction (type 2 hypersensitivity)

CHRONIC DISCOID LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Discoid Lupus Erythematosus (DLE) is a common subtype of cutaneous lupus

It is 2-3 times more common than SLE and typically has an onset between 20-40 years of age

It is observed more frequently in individuals of Asian and African ancestry

KEY CLINICAL FEATURES

If you suspect a patient might have discoid lupus but are not sure (eg scarring alopecia, facial rash) look in the conchal bowls as they might be affected which would suggest lupus

HISTOPATHOLOGY

Hyperkeratosis

Epidermal atrophy

Prominent follicular plugging

Basal layer vacuolar changes

Basement membrane thickening (best seen on PAS stain)

There is a lymphocytic infiltrate in the superficial and deep dermis and around dermal blood vessels and appendages

Dermal mucinosis is also observed

Positive DIF in lesional skin in 90% and usually negative in non-lesional skin

CDLE ASSOCIATION WITH SLE

It is key to differentiate whether this is localised DLE versus genearlised DLE

Approximately 5% of those with localised DLE will develop SLE

Approximately 15% with generalised DLE will develop DLE

This estimate is higher in children (approx 25-40%)

So if disseminated lupus is present you may need to be more vigilant about thinking about SLE (eg performing systems review and Urine PCR when in clinic)

SUBACUTE CUTAENOUS LUPUS

Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus (SCLE) is an umbrella term for a type of cutaneous lupus that dermatologists commonly encounter in clinic, second only to discoid lupus

It is characterized by a photosensitive papulosquamous or annular polycyclic eruption that does not typically scar

More common in females: F:M ration 4:1. Typical average onset of age 30 years

CLINICAL FEATURES

SCLE lesions often appear annular and are found in an extensor distribution, frequently affecting sun-exposed areas like the V of the neck (although it can extend beyond this sun exposed sites)

Annular lesions can join up and become polycyclic

Usually don’t scar

They can show varying degrees of scale but are generally less indurated and thick compared to discoid lupus

It can sometimes present as a psoriasiform rash in a photosensitive distribution, which might prompt consideration of subacute lupus

Facial involvement can include the classic butterfly rash - photo-protected areas such as behind the ears, naso-labial areas and under the chin will often be spared

When get dorsal hand involvement you tend to get a flat erythema affecting the skin between the joints of the hand in comparison to Dermatomyositis which affects the joints

Can also get prominent nail fold erythema

Histopath:

Can appear similar to histopathology of Discoid lupus but the inflammation generally tends to be less dense

ASSOCIATION WITH SLE

Has a larger association with SLE than Discoid Lupus

Approx 50% of SCLE cases are associated with SLE based purely on ACR criteria

However, the rate of true organ involvement is likely lower estimated at 15-20%

When systemic disease is present in SCLE patients, it is generally mild, with severe manifestations like nephritis or cerebral disease being rare

ASSOCIATED ANTIBODIES

Most patient with SCLE have positive antibodies

ANA ≈ 80%

Ro/SSA antiboddy ≈ 80%

La/SSB antibody ≈ 40%

Levels of dsDNA antibody typically low (≈ 5%)

ESR often raised and can have FBC abnormalities

DRUG-INDUCED SCLE

Often affects older patients

F:M 9:1

Indistinguishable by clinical appearance from SCLE

Onset is often delayed (can be many months after starting the culprit drug)

Resolution after discontinuing the drug can be slwo with a mean of 4-6 weeks (if it persists beyone one year it may not be drug-induced

Common causes:

PPIs (omeprazole)

Thiazide diuretics

Calcium channel blockers

Terbinafine

Drug-induced SCLE is associated with anti-histone antibodies in approximately 30% of cases only

ACUTE CUTANEOUS LUPUS ERYTHEMATOSUS

Again acute cutaneous lupus is an umbrella term and it encompasses:

Localised acute CLE (Malar rash)

Generalised acute CLE

Bullous LE

TEN-like CLE

ACLE is almost associated with SLE

Localised acute CLE (Malar rash):

This presentation typically manifests as a malar or ‘butterfly’ rash distributed on the cheeks and across the bridge of the nose with sparing of the naso-labial areas, It can be flat or papular and may resemble rosacea

Photosensitivity is a common feature, though patients might not report it due to a delayed onset of exacerbation (days to weeks) after sun exposure - so sometimes asking if symptoms worsen in summer or winter can be helpful

Generalised acute CLE:

A diffuse or papular erythema on the face, V of neck, extensor forearms (spares knuckles)

It can resemble or morbilliform drug eruption or viral exanthem

Bullous Lupus Erythematosus (Bullous LE):

Bullous LE presents with tense bullae or erosions, primarily on sun-exposed areas

Pruritus is often minimal or absent

These lesions typically heal without scarring

Antibodies bind to Type VII colalgen at the DEJ

This results in an immunoflourescence pattern similar to Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita on salt split skin

Differences between bullous lupus and EBA:

It occur on sun exposed sites

Lack of scarring

Less prominent mucosal lesions

TEN-like CLE:

Clinically, TEN-like CLE is very similar to drug-induced Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis (TEN), presenting with widespread epidermal necrolysis

While active lupus can be a pointer, patients with connective tissue disease are also more susceptible to drug rashes and exposure to causative medications, making differentiation difficult

Reported cases suggest it may be photodistributed or photoexacerbated/triggered

Distinghishing features:

May have less pronounced mucosal involvement in TEN-like lupus

May see interface change on biopsy (as well as keratinocyte necrosis)

May see immunoprecipitants at the BMZ in acute lupus (which might not be seen in typical TEN)

LUPUS TUMIDUS

Lupus tumidus is a distinct form of cutaneous lupus, though its exact placement within the classification of LE is debated

Some authors consider it a form of lupus due to its interferon signature, the involvement of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), and its photoexacerbation

It is often debated how it relates to Jessner’s lymphocytic infiltrate, but tumid LE is generally considered more photosensitive and if generally very responsive to hydroxyhloroquine

Clinically, lupus tumidus presents as violaceous, indurated nodules or plaques

They are commonly seen on sun-exposed sites like the face and chest

A key feature is minimal surface change, as the underlying pathology involves intense inflammation in the deep dermis

Association with SLE:

Low association with SLE (5%)

In patients with lupus tumidus, routine blood tests like FBC are typically normal, and ANA/Ro antibodies are often negative

TREATMENT

The aim of treatment is to control disease activity and minimise the risk of scarring

There are BAD guidelines from 2021 regarding the management of cutaneous lupus:

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/bjd.20597

General principles:

Smoking cessation

Cigarette smoking highly prevalent in CLE patients (60-80%) and is associated with increased disease activity and damage

It also interferes with effectiveness of anti-malarial treatment

Strict photoprotection

Sunscreen: Covering for UVA and UV, use throughout Winter also

Sun protective clothing

Other physical blocks (eg uv blocking films on car windows)

Latency period between sun exposure and development of lesions can range from days to weeks so often patient might not notice association

Could consider Vitamin D supplementation (due to need for extensive photoprotection)

LOCAL TREATMENT

Topical corticosteroids

Very potent/potent topical steroids for localised DLE inlcuding lesions on the face

Can. use daily, for up to 4 weeks and once it has responded consider reducing the frequency to twice-weekly maintenance

Review effectiveness after 3-6 months

Can also use as an adjuvant to systemic therapy for widespread cutaneous involvement

Topical calcineurin inhibitors

Can be offered as first line mono-therapy for localized DLE for up to 12 weeks

Consider reducing to twice-weekly dose for maintenance dose once response is achieved

Intralesional triamcinolone

Can consider for localised DLE or for persistent lesions (particularly useful for scalp lesions)

Give 0.1ml per 1cm2 field of triamcinolone with the following concentration - 2.5-5mg/ml for sites with higher risk of atrophy (eg face) and 10mg/ml for other areas

SYSTEMIC TREATMENT

FIRST-LINE SYSTEMIC TREATMENT

HYDROXYCHLOROQUINE

Dosing:

Can take 6-12 weeks to show full effect

Offer doses at 200-400mg daily

BAD guidelines suggest that the daily maintenance dose should not exceed 5mg/kg (actual body weight)

Opthalmology monitoring (RCOG guidelines):

Annual screening for retinopathy is recommended for all patients who have taken HCQ for more than 5 years

Screening should include spectral domain optical coherence tomography and fundus autofluroescence imaging photography

Annual screening may start after 1 year of treatment if additional risk factors for retinal toxicity are present:

Concomitant tamoxifen

Impaired renal function (eGFR < 60ml/min)

Daily dose > 5mg/kg

Chloroquine use

MEPACRINE

Consider mepacrine (50-100 mg daily) as an alternative first-line antimalarial, especially if there are concerns about retinal toxicity with HCQ - It has a lower risk of retinal toxicity compared to HCQ

Can also be considered as an add-on therapy if HCQ monotherapy is not fully effective

Some patients may notice a slight yellow tinge to the skin

GPP in guidelines: Exercise caution when using maximum doses of HCQ and when using them in combination with mepacrine due to uncertainties surrouding retinal safety with such combinations

CHLOROQUINE

Third-line antimalarial option

Clinical trials suggest it is highly effective but it carries a significantly higher risk of retinal toxicity compared to HCQ (up to 30 times)

It is rarely prescribed in clinical practice as a result

CORTICOSTEROIDS

Consider concurrent tapering dose of oral prednisolone (eg 0.5mg/kg for 2-4 weeks with gradual dose reduction) or IV methylprednisolone to try to control severe or widespread CLE while waiting for antimalarials to take effect

SECOND-LINE SYSTEMIC TREATMENT

METHOTREXATE

Consider MTX (up to 25mg once weekly) in patients whose CLE shows an inadequate response to topical therapy and antimalarials

Can use it in combination with antimalarials

Subcutaneous MTX may be more effective due to earlier achievment of maximum dosage

For severe cutaneous lupus, MTX appears effective in about 60% of patients

MYCOPHENOLATE MOFETIL

Can be considered an alternative treatment option for those patients who cannot tolerate/are not suited to MTX

Consider MMF (typically initiated at 500mg bd and escalated to 1.5g twice daily, depending on response and tolerability) in patients with an inadequate reponse to topical therapy and antimalarials

MMF can be combined with antimalarials

If get significant GI side effects, consider switching to enteric-coated mycophenolate sodium (360mg equivalent to 500mg MMF)

DAPSONE

Can consider as a second-line systemic treatment option for CLE

Can also be considered a first-line option for SCLE and bullous SLE as seems to work well in these conditions

ACITRETIN

Consider acitretin (25-50MG daily) as a second-line systemic treatment option for CLE

It can specifically be considered for hyperkeratotic DLE that is resistant to topical therapy and anti-malarials

May be useful in males or women not of non-child bearing age who failed on hydroxychloroquine (+/- mepacrine) and should only be offered to individuals of child-bearing potential in exceptional circumstances

THIRD LINE SYSTEMIC AGENTS

These options are typically reserved for treatment-resistant disease after conventional therapies have failed.

BELIMUMAB

BAFF (B-cell Activating Factor) inhibitors such as belimumab are IgG monoclonal antibodies that work by binding to and neutralizing the soluble BAFF cytokine, which is essential for B-cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation into antibody-producing plasma cells.

In lupus, excessive BAFF signaling leads to overproduction of pathogenic autoantibodies (eg anti-dsDNA, anti-Smith, and anti-Ro antibodies) that form immune complexes.

By neutralizing soluble BAFF, belimumab leads to:

Reduced survival of autoreactive B cells and

Decreased differentiation of naïve B cells into plasma cell

This ultimately leading to reduced autoantibody production.

Of note, belimumab does not significantly deplete all B cells (unlike CD20-depleting agents such as rituximab), but rather modulates their survival

In the UK, its use is restricted to patients with active seropositive SLE

So while there is insufficient evidence for its use specifically in CLE, you can consider belimumab in eligible patients with SLE who also have cutaneous involvement, particularly when conventional systemic therapies have failed

RITUXIMAB

In two pivotal trials for SLE Rituximab failed to meet all primary outcomes

EXPLORER - Non-renal SLE (2010)

LUNAR - Lupus nephritis (2012)

In the UK, NHS England has approved it for its use in SLE

BAD guidelines state that there is insufficient evidence to support its routine use in CLE but it can be considered on a case-by-case basis in people with treatment resistant CLE where conventional treatments have failed

OTHER THIRD LINE THERAPIES

IVIG

Thalidomide - Has been looked at in older studies. May have a degree of efficacy but there are multiple side effects associated with it such as peripheral neuropathy, teratogenicity and risk of thromboembolism

Lenalidomide - safer then thalidomide but extremely expensive

POTENTIAL FUTURE TREATMENTS

ANIFROLUMAB

Anifrolumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody that targets the type I interferon receptor subunit 1 (IFNAR1)

It’s used primarily in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Anifrolumab blocks type I interferon signaling, which is a key pathogenic pathway in lupus. Up to 80% of patients with SLE exhibit an “interferon gene signature,” indicating overactivity of this pathway.

Given by 300 mg IV infusion every 4 weeks.

Shown in the TULIP-1 and TULIP-2 trials to significantly improve disease activity as measured by the BICLA (British Isles Lupus Assessment Group–based Composite Lupus Assessment) response.

Benefits include reduced steroid doses and improved skin and joint outcomes.

Is currently undergoing trials for its efficacy in cutaneous lupus