Clinical appearance (based on size of vessel affected)

Small vessel vasculitis:

Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis

Small and medium vessel vasculitis:

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s)

Eosinophilic granultomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg Strauss)

Medium vessel vasculitis:

INTRODUCTION

Vasculitis is inflammation directed towards the blood vessel wall

It can occur in any organ of the body

It can be limited to the skin or it can be a manifestation of a systemic vasculitis

Can get vasculitis of arteries, veins, capillaries

How it presents depends on the size of blood vessel affected and current classification is based on the size of the blood vessel involved

Cutaneous involvement in the majority of cases tends to affect the small and medium sized vessels

PATHOGENESIS

Terms:

Cutaneous small vessel vasculitis (CSVV) refers to a vasculitis involving primarily dermal post-capillary venules and when a biopsy is taken you see a specific histological pattern of vasculitis called leucocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV)

In LCV the postcapillary venules of the dermis are affected by an intense neutrophilic vascular inflammation

LCV often used interchangeably with CSSV but LCV however:

LCV can be seen in settings of mixed small and medicum vessel vasculidities (eg Granulmatosis with polyangiitis) whereas the term CSVV should generally be reserved for when only small vessels are involved (without any mixed sized vessel involvement)

Leucocytoclastic vasculitis on biopsy:

Neutrophils around blood vessels

Leucocytoclasis (degnerating neutrophils) forming ‘nuclea dust’

Fibrinoid necrosis (within vessel wall, looks pink)

Extravasated red cells

Small and medium vessel vasculidities tend to be either an immune complex mediated vasculitis or an ANCA associated vasculitis

Immune complex mediated vasculitis pathology:

All forms of CSVV and some forms of mixed and medium-sized vessel vasculidities are mediated by immune complexes (type 3 hypersensitivity reaction)

Essentially an antigen (eg a virus) is bound by antibodies and forms immune complexes

These deposit into postcapillary venules in the skin

These lodged complexes then activate complement which attracts neutrophils which damage the blood vessels allowing red blood cells to leak out

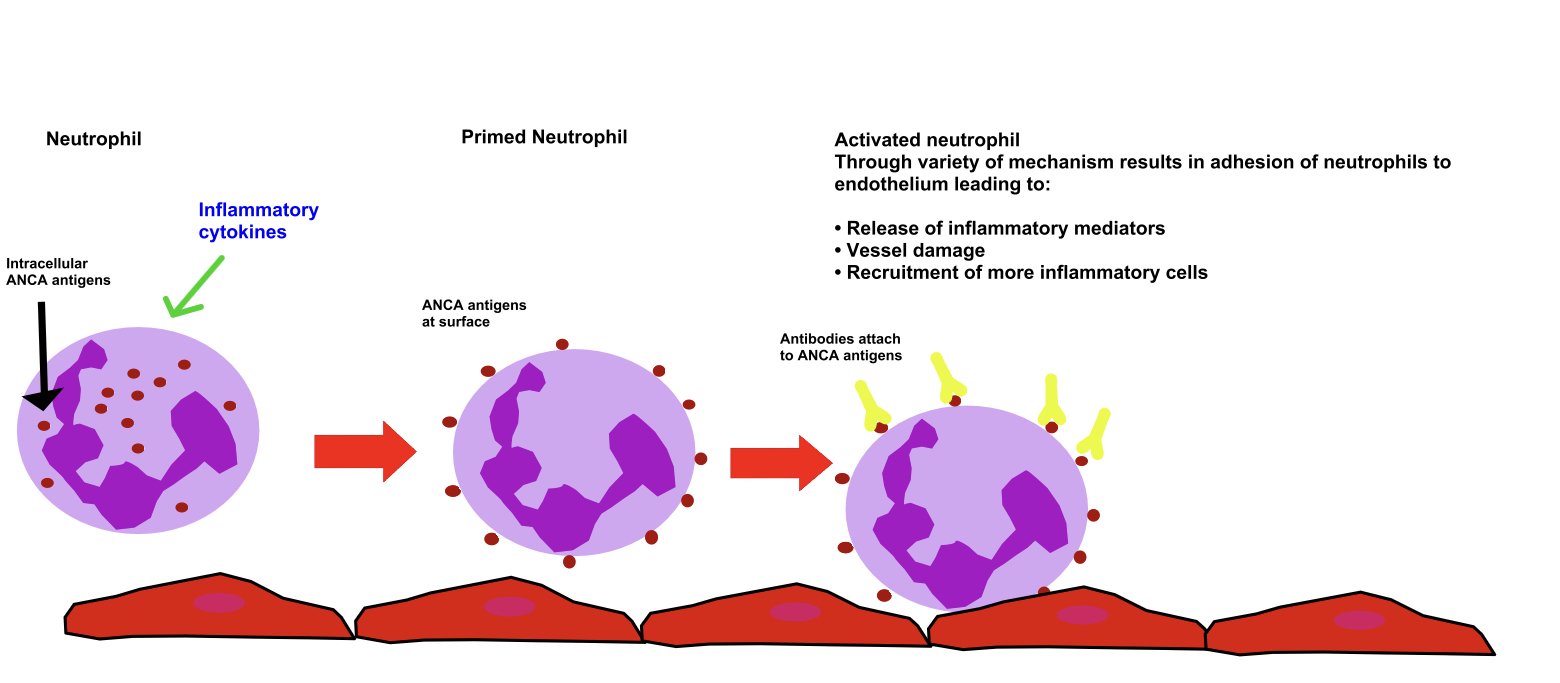

ANCA associated vasculitis pathology:

The ANCA associated vasculidities are not mediated by immune complexes

PR3 and MPO are intrecellular neutrophillic proteins that can translocate to the neutrophil cell surface after activation by cytokines (eg TNFα)

An ANCA antibody can then bind to these antigens resulting in adhesion of neutrophils to the blood vessel endothelium

This results in release of inflammatory mediators, vessel damage and recruitment of additional inflammatory cells

As there is a lack of immune complex deposition on immunoflourescence we call this pauci-immune

CLINICAL APPEARANCE (based on size of vessel affected)

Small Vessels:

Arterioles, capillaires, postcapillary venules

Superficial and mid dermis

Skin manifestations:

Palpable purpura

If gently feel around area, it will feel raised

Non-blanching

Macular purpura

Petechiae

Urticarial papules

Vesicles

Pustules

Targetoid papules and plaques

Dr. McColl

Palpable purpura

Courtesy Dr. Mccoll

Medium Vessels:

Small arteries and veins

Deep dermis and subcutis

Skin manifestations:

Livedo racemosa

Retiform purpura

Ulcer

Subcutaneous nodules

Digital necrosis

So can get a patient with manifestations of:

Small vessel signs only

Medium vessel signs only

Combination of both

CLASSIFICATION

Clinically (+/- histologically) should give consideration to what size of vessels are affected as this may give a clue to the underlying cause

Classification by size (Chapel Hill classification)

Small vessels:

Idiopathic cutaneous small vessel vasculitis

Secondary cause of cutaneous small vessel vasculitis

Drugs

Infection

Malignancy (usuallly haematologic)

Urticarial vasculitis

Henoch-schonlein purpura

Acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy

Erythema elevatum diutinum

Small and medium vessels:

Cryogloulinaemia (Type II and III)

ANCA-associated

Microscopic polyangiitis (MPA)

Wegener’s granulomatosis (GPA)

Churg-Strauss (EGPA)

Secondary causes

Infection

Inflammatory disorder (eg autoimmune connective tissue disease)

Medium sized vessels:

Poyarteritis nodosa (PAN)

Classic (systemic) PAN

Cutaneous PAN

Large sized vessels:

Temporal arteritis

Takayasu’s arteritis

Other considerations when classifying cutaneous vasculitis:

Look for underlying causes

? ANCA positive or negative

Direct immunoflouroescence findings: Especially ? IgA predominance

Evidence of systemic manifestations

REVIEW OF SYSTEMS

If there is concerns about a systemic vasculitis a thorough review of systems should be performed in history for past and present symptoms.

Constitutional: Fever, weight loss, night sweats, arthralgias

URTI

Oral/nasal ulcers

Nasal perforation, saddle nose deformity

Sinusitis

Hearing loss/recurrent otitis media

Change in voice (vocal cords)

Subglottic stenosis

Eyes

Psueotumours

Conjunctivitis

LRTI (lung infiltrates, cavities, haemorrhage)

Can be sudden and acute or chronic

Shortness of breath, cough haemoptysis, pleuritis

Cardiac (myocarditis/pericarditis)

Chest pain, shortness of breath, palpitations

GIT:

Abdominal pain

Change in bowel habits

Blood pr

Kidneys: (Glomerulonephritis, vascular occlusion)

Urine dipstick blood, protein, casts

Urine Protein:creatinine ratio

Peripheral neuropathy

Motor (eg foot drop)

Sensory

CNS changes

Stroke like symptoms

Skin changes

Palpable purpura

Livedo reticularis

Nodules

Ulceration

Necrosis

VASCULITIC SCREEN

When assessing for a vasculitis it is important to look for any kidney damage and is essential to check and monitor blood pressure and perform a a urine dipstick

If the urine dipstick shows protein and/or blood it is important to send for urinary protein:creatinine ratio

Also may perform ‘vasculitic screen’, an example of a vasculitic screen that could be considered would be:

FBC

U&E/LFT

CRP/ESR

Antibodies: ANA, ENA, dsDNA, RF

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibodies (ANCA)

Complement levels

Cryoglobulins

Hepatitis B/C, HIV serology

Immunoglobulins

Serum electrophoresis

Anti-streptocccal titre (ASOT)

Skin biopsy with samples sent for H&E and direct immunofluorescence (DIF)

Ideally performed in first 24-48 hours

DIF:

+ve in 80% CSVV

+ve 100% lesions < 24 hours old

+ve 30% at 48-72 hours

Only C3 > 72 hours

Granular pattern within vessel wall

C3, IGM, IgA +/- IgG

Negative in ANCA associated vasculitis

CUTANEOUS SMALL VESSEL VASCULITIS (CSVV)

As mentioned previously it involves primarily dermal post-capillary venules and it is charachterised histologically by a leucocytocastic vasculitis

The term CSVV is generally reserved only for when small vessels are involved (without medium sized vessel involvement )

Causes:

Idiopathic (45-55%)

Infection (15-20%)

Bacterial - Group A strep

Viral - Hepatitis B/C, HIV

Fungal - Candida

Inflammatory (15-20%)

Autoimmune onnective tissue disease: RA, SLE, Sjogen’s

IBD

Seronegative spoindylarthropathy

Drug (10-15%) (following list not exhaustive)

Anti-inflammatories:

NSAIDs

COX-2 inhbitors

Antibiotics:

Beta lactam antibiotics

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole

Quinolones

Vancomycin

Allopurinol

Cardiac medications

Diuretics: thiazides, loop

ACEi, beta blockers

OCP

Neoplasm (5%)

Often haematological but can be due to solid organ cancers also

Within the spectrum of CSVV there are several subtypes with unique features:

Henoch schonlein pruprua

Acute haemorrhagic oedema of infancy

Urticarial vasculitis

Erythema elevatum diutinum

CSVV clinical features:

Typically present 1-2 weeks after exposure to inciting agent

Usually presents with palpable purpura and petechiae on dependant areas such as the lower legs and pressure points

Can also present as:

Urticarial lesion

Vesicles

Pustules

Targetoid lesions

Lesions often more severe in areas under pressure (eg sock line)

Can be itchy +/- painful

Residual postinlfammatory hyperpigmentation may persist for months after primary process resolves

Extracutaneous involvement can occur (eg fever/arthralgias, gastrointestinal or genitourinary involvement) but is uncommon and usually mild

Prognosis:

90% will have spontaneous resolution of cutaneous lesions within weeks/few moths

10% will have chronic or recurrent disease at intervals of months to years

Assessment:

Determine if patient has particular sub-type of CSVV (eg HSP)

Outrule a systemic vasculitis syndrome

Consider secondary causes

Treatment:

It often resolves without any treatment

Remove inciting trigger

Supportive measures:

Leg elevation, avoid tight clothing, rest

Symptomatic therapy:

Antihistamines, NSAIDs

Chronic disease (> 4 weeks) or more severe cutaneous disease consider:

Colchicine 0.6mg bd-tds (often get GI side effects)

Dapsone 50-200mg/day

Can consider both in combination

Severe, ulcerating or progressive cutaneous disease needing rapid control:

Short course of systemic oral steroids

Up to 1mg/kg/day

Taper over 4-6 weeks

If recurs when dose is tapered or disease is recalcitrant may need steroid sparing agent

Methotrexate

Azathioprine

HENOCH SCHONLEIN PURPURA

HSP is an IgA vasculitis (IgA predominance seen on immunoflourescence)

It is the commonest form of vasculitis in children

(90% occur in children < 10 years)

Children classically initially have a URTI or strep infection

1-2 weeks later symptoms and signs

Evidence of medium vessel disease or widespread lesions (including face) could indicate an underlying IgA paraproteinaemia

HSP tetrad:

1. Palpable purpura legs and buttock

2. Arthralgia of knees and ankles

3. GI issues including abdominal pain and diarrhoea with or without melena

4. Renal changes with haematuria, possible nephritis and rarely renal failure (1% of cases)

HSP clinical findings:

Cutaneous findings:

Erythematous papues/plaques evolving to palpable purpura is classical finding

Urticaria, vesicles, bullae and foci of necrosis can be seen

Typically symmetrical and distributed on buttocks and lower extremities

Can involve trunk, upper extremities, face

Individual lesions last 10-14 days with skin resolution over weeks-months

Can get recurrent skin disease in 5-10% of patients

Arthritis:

Up to 75% of patients

Commonly joints of lower extremities (knees and ankles)

Gastrointestinal::

50-75% of patients

May precede purpura

Colicky abdominal pain

Vomiting

GI bleeding (30%)

Rarely - intussusception and bowel perforation

Renal:

40-50% of patients

Microscopic haematuria (40$)

Proteinuria (25%)

Cutaneous lesions often precede nephritis but latter usually clinically evident within 3 months

Persistent renal disease (requiring monitoring till resolution) in 30-50% of patients

Only 1-3% of children develop long-term renal impairment

Orchitis:

Can rarely occur in young boys

Poor prognostic features HSP:

Renal failure at time of onset

Nephrotic syndrome

Hypertension

IgA small vessel vasculitis adults (sometimes called adult HSP)

Clinical presentation and prognosis differ to children

Necrotic skin lesions present in 60% of adults (vs <5% children)

Up to 30% may develop chronic renal insufficiency

3 findings suggestive that an adult with HSP will have kidney involvement with a IgA glomerulonephritis:

1. Fevers

2. Increased ESR

3. Purpura located above the waist (‘think purpura getting close to kidneys so more likely to be involved’)

Adults more likely to require more aggressive therapy

If IgA vasculitis due to cancer 60-90% is due to solid organ cancer (particularly lung)

This is in contrast to most CSSV in which cancer is usually haematologic

Diagnosis:

Biopsy: leucocytoclastic vasculitis

DIF: IgA deposition in blood vessel walls so many people recommend to do biopsies in rashes suspicious for vasculitis as it will give an indication if we need to monitor for renal disease as time goes by

(IgA can be seen in other types of CSSV so diagnosis of HSP supported by IgA predominance)

Monitoring:

Serial urinalysis (+/- urine pcr)

Check faecal occult blood if have GI symptoms

Treatment:

Disease usually self-limited and resolves over weeks to months

Supportive

Dapsone or colchicine may decrease duration of cutaneous lesions

Systemic steroids can treat the arthritis, the abdominal pain and duration of skin lesions (but do not prevent skin recurrence)

Refer to nephrology if evidence of renal involvement as treatment

They could consider ACEi, steroids or other treatments

URTICARIAL VASCULITIS

Clinical presentation resembling urticaria but see LCV on histopathology

Often idiopathic but can be associated with:

Autoimmune connective tissue disease: SLE, Sjogren’s, RA

Infections - HBV, HCV, EBV

Serum sickness

Medications - NSAIDs, fluoxetine, potassium iodide

Malignancies - usually haematological

Cutaneous features:

Unique from regular urticaria in that:

1. Urticarial papules and plaques last > 24 hours

2. More pain and burning than itch

3. May have residual haemorrhage

4. May esolve with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation

5. May have systemic symptoms (See below)

Rarely presents as: Bullae, EM like lesions, Livedo reticularis

Can be associated with or without angioedema

Urticarial vasculitis further broken down in to:

Normocomplementaemic (3/4 of cases)

Mostly skin limited

Average duration 3 years

Hypocomplementaemiac (1/4 of cases)

Hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis is more likely to be associated with systemic changes with the following systems involved:

Arthralgia

Of hands, elbows, knees and ankles in 50% of patients with urticarial vasculitis

50% of patients with HUVS (see below) have frank arthritis

Pulmonary

Up to 20% have pulmonary symptoms - cough, laryngeal oedema, haemoptysis, asthma, COPD

The COPD is especially severe in smokers with urticarial vasculitis

GI

30% of patients

Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea

Renal

5-10% of patients with HUVS

Look for proteinuria/haematuria

Ocular

Uveitis/episcleritis occurs in HUVS

Hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis syndrome (HUVS) is a more severe syndrome defined by specifc diagnostic criteria:

Patients with hypocomplementaemia who don’t meet the above criteria have hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis but not HUVS

They are not thought to transition from one to another

Common abnormal labs urticarial vasculitis:

High ESR

Low C3, C4 and CH50 (this is decreased if components of classical complement pathway are low)

HUVS marked by:

Low serum complement

Plus presence of anti-C1q antibody and low C1q levels

HUVS and SLE:

HUVS can share features with SLE

Distinctive clinical findings in HUVS are:

Ocular inflammation (30%) - conjunctivitis, episcleritis, iritis,uveitis

Angioedema (>50%)

COPD like symptoms (50%)

Lab findings HUVS and SLE:

1/3 patients with SLE have anti-C1q antibodies

Up to 1/2 patients with HUVs have positive ANa

But patients with HUVS rarely have anti-dsDNA or anti-Sm antibodies

Diagnosis urticrial vasculitis:

H&E:

Finding of leucocytoclastic vasculitis is essential for diagnosis of urticarial vasculitis

(can often be subtle)

DIF:

70% Immunoglobulin, C3 or fibrin around blood vessels

Can see granular pattern along basement membrane in 80% of lesions - if this is accompanied by hypocomplementaemia this may be suggestive of a diagnosis of SLE

Treatment:

No RCTs

Antihistamines may reduce swelling and pain associated with lesions but do not alter course

Considerations:

Oral steroids effective but keep duration to a minimum

NSAIDs: indocmethacinDapsone

Colchicine

Hydroxychloroquine

MMF

Rituximab or IVIG may also be useful for recalcitrant hypocomplementaemic urticarial vasculitis

Schnitzler’s syndrome:

• Urticarial vasculitis

• Monoclonal IgM gammopathy

and at least two of the following:

Fever (periodic)

Arthralgia

Hepatosplenomegaly

Increased ESR

Increased WBC

Bone abnormality

Bone pain

Resolve with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation

Cryoglobulinaeimas:

Cryoglobulins are immunoglobulins that precipitate in the cold

Cryoglobulinaemia broken down in to 3 types:

Type 1:

Doesn’t cause a vasculitis

Usually due to monoclonal IgM (Less frequent IgG which is > than IgA)

Symptoms and signs due to ‘sludging’ of the blood vessels with microvascular occlusion

◦ Associated with plasma cell dyscrasias and lymphoproliferative disorders

◦ Present with:

‣ Livedo reticularis

‣ Raynaud’s

‣ Acrocyanosis

‣ Retiform Purpura

Type 2 and 3 - ‘mixed cyroglobulinaemias’

Approx 15% of patients with circulating mixed cryoglobulins present with symptoms due to cryoblobuniaemic vasculitis

Antibodies combine to form immune complexes which deposit in the blood vessels which activates complement causing a leucocytoclastic vasculitis

Causes a vasculitis that can involve both small and medium-sized vessels (preferentially small)

It typically affects:

Skin

Peripheral nervous system

Kidneys

Type 2 cryoglobulinaemias exhibit monoclonal IgM or IgG directed against polyclonal IgG

Type 3 cryobloulinaemia exhibit polyclonal IgM against polyclonal IgG

Occurs in setting of -

Infections:

Hepatitis C virus accounds for 70-90% of cases

>50% of patients with HCV infection have cryoglobulinaemia

Overt cryogloublinaemic vasculiltis develops in approx 5% of these cases

Higher prevalence in Southern Europe as increased prevalence HCV here

Hepatitis B virus (5% of cases)

EBV, CMV, Leishmania, Trepenoma

2. Connective tissue diease:

RA

Sjogrens

Systemic sclerosis

3. Lymphoproliferative disorder (5%)

B-cell non-hodgkin lymphoma

CLL

Macroglobulinaemia

Rarer: solid tumours (HCC)

Clinical cryoglobulinaemic vasculitis:

Cutaneous:

Commonest to have palpable purpura of lower extremities

Can see ecchymoses and dermal nodules

Rarer: urticaria, livedoe reticularis, necrosis, ulceration, bullae

Not typically cold induced (in contrast to vascular occlusive lesions in type 1 cryoglobulinaemia)

Arthritis - 70%

Peripheral neuropathy - 40% (typically sensory)

GI disease or hepatitis - 25%

Rarer:

Xerostomia/xerophthalmia

Endocrine issues (thyroid/gonads)

Investigations:

Elevated cryoglobulins

Can be falsely negative

Need to check during clinical flares and on more than one occasion

Blood sample should be kept warm at 37°C until it is spun in the lab to avoid a false negative

Check with lab their protocol prior to collecting cryoglobulins

Rheumatoid factor - is positive in 70-90% cases

Is an easier test to perform than cryogloublins

RF by definition is an autoantibody against the Fc portion of IgG

Fc portion is the bottom of the Y shape of the antibody

Types 2 and 3 mixed cryobloulinaemias consist of immune complexes containing antibodies to IgG so you often get positive RF

ANA - 20% positive

Complement - often low or undetectable C4

SPEP - 15% with mixed cryoglobulins have monoclonal gammopathy

Hepatitis and HIV serology

Pathology:

H&E:

Leucocytoclastic vasculitis

DIF:

Granular deposits of predominantly IgM and C3 in a vascular pattern observed in papillary dermis

Treatment:

Treat hepatitis C infection

Interferonα pluse ribavirin often can lead to resolution of cutaneous (100%), renal (50%) and neurological manifestations

I rare cases interferon can make the peripheral neuropathy worse

Considerations if severe:

Plasma exchange

Cyclophosphamide

Rituximab

ANCA associated vasculitis

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener’s granulomatosis)

Microscopic polyangiitis

Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg Strauss)

Together these conditions have annual incidence of 20 cases per million people in N. America and Europe

Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) refer to IgG auto-antibodies that target antigens in the cytoplasm of neutrophils (mostly) and monocytes

To improve specificity two tests are usually done on a patients blood:

Indirect immunoflourescence on a patient’s neutrophils can demonstrate two vasculitis relevant patterns of staining:

cytoplasmic: c-ANCA

perinuclear: pANCA

ELISA which can specifically detect antibodies to the relevant antigens

Proteinase 3 - anti-PR3 antibodies

Myeloperoxidase - anti-MPO antibodies

ELISA can detect the amount of antibody present as a titre

The higher the titre, the more antibody there is (ie 1:64 > 1:8)

About 85% of patients with cANCA pattern have PR3 antibodies

About 90% of patients with pANCA pattern have MPO antibodies

Often do IIF first which detects pANCA or cANCA staining and if positive you then do ELISA to specifically detect anti-PR3 antibodes or anti-MPO antibodies

However, up to 5% of serum samples are positive for ELISA only so if there is a high index of suspicion for ANCA associated vasculitis should perform ELISA even if IIF is negative

Anti-PR3 ANCA:

+ve in up to 90% of patients with GPA (Wegener’s)

+ve in 30% of patients with MPA

Anti-MPO ANCA:

+ve in 60% of patients with MPA

+ve in 60% of patients with EGPA (Churg-Strauss)

Can use ANCA for disease monitoring and also for checking response to treatment

Presence of ANCA within first year following remission has been associated with disease relapse

Pathogenesis:

PR3 and MPO are intrecellular neutrophillic proteins that can translocate to the neutrophil cell surface after activation by cytokines (eg TNFα)

An ANCA antibody can then bind to these antigens resulting in adhesion of neutrophils to the blood vessel endothelium

This results in release of inflammatory mediators, vessel damage and recruitment of additional inflammatory cells

As there is a lack of immune complex deposition on immunoflourescence we call this pauci-immune

Prognosis:

Morbiditiy and mortality of ANCA-associated vasculidities are relatively high due to:

Systemic manifestations disease

Complications of immunosuppressive therapy

Poor prognostic factors:

Delay in diagnosis

Renal impairment

Propensity for relapse

Older age

Presence of ANCA

Workup for systemic vasculitis:

Do extensive history for past and present clinical features (including)

Once a diagnosis is made the severity of the disease should then be assessed

Is it limited: eg chronic ENT disease

Is it severe (organ or life threatening): renal, pulmonary or neurological disease

Treatment is aimed at:

Remission induction

To switch off the vasculitis activity

Done over a course of 3-6 months

Remission maintenance

To keep disease under control

The treatments for the various ANCA vasculidities in general are quite similar

GRANULOMATOSIS WITH POLYANGIITIS (formerly Wegener's granulomatosis)

Chronic systemic vasculitis

Small and medium sized arteries affected

Classic triad of symptoms for granulomatosis with polyangiitis:

1. Upper respiratory disease

2. Lower respiratory disease

3. Renal disease

Clinical findings:

Peak incidence age 30-50

Can involve multiple organ systems

MICROSCOPIC POLYANGIITIS

Can have quite similar clinical findings to GPA but without:

The granulomas

The upper respiratory findings

The progressive clinical course of MPA typically leads to renal failure and/or pulmonary haemorrhage

Antibodies:

Anti-MPO antibodies +ve 60% of patients

Anti-PR3 antibodies +ve 30% of patients

Skin biopsy:

Segmental necrotising vasculitis of small blood vessels and to lesser extent medium-sized arteries

No evidence of granulomatous inflammation

Treatment:

2 phases:

Induction of remission

Maintenance therapy

Induction remission:

Steroids initially (1mg/kg/day pred)

Addition of cyclophsphamide with significant organ involvement (renal, pulmonary, neurologic)

Can give cyclophosphamide for 6 months (orally 2mg/kg/day or IV Pulses 0.5-1g/m2/month)

Pulse therapy reduces total drug dose and incidence of side effects (eg bladder cancer)

Recent data suggest corticosteroids plus rituximab may be equally effective as steroids/cyclophosphamide

Maintenance of remission:

Methotrexate

Azathioprine

MMF

IVIG

Plasma exchange can be considered in ANCA-positive patients

Biologics (eg infliximab) has shown promise but further evidence required

Prognosis:

Higher rate of relapse compared to classic PAN (regardless of severity)

Lower rate than those with Wegener’s

Persistence of ANCA despite induction of remission associated with increased risk of relapse

EOSINOPHLIC GRANULTOMATOSIS WITH POLYANGIITIS (formerly Churg-Strauss syndrome)

Granulomatous small vessel vasculitis affecting mainly blood vessels of:

Lungs (severe asthma, allergic rhinitis)

GI tract

Peripheral nerves

Lesser extent:

Skin

Heart (leading cause of death)

3 phases:

1st phase - symptoms of allergic rhinitis, nasal polyps and asthma persisting for years

2nd phase - peripheral eosinphilia, respiratory tract infections, GI symptoms

3rd phase - Systemic necrotizing vasculitis with granulomatous inflamamtion which can occur several years to decades after initial symptoms

Investigations:

Elevated IgE

p-ANCA

Anti-myeloperoxidase +ve in 60%

POLYARTERITIS NODOSA

Necrotising vasculitis of medium sized muscular arteries

Comes in 2 presentations:

1. Classic systemic form

2. Cutaneous PAN (limited systemic involvement)

PAN can affect multiple organs but tends to spare one organ: the lung

Clinical:

Skin changes:

Palpable purpura lower legs

Painful subcut nodules following course of blood vessels

Lacy livedo reticularis interspersed amongst these purpura and nodules

PAN can affect multiple organs but tends to spare one organ - the lung

Kidney damage is due to issues with perfusion

Don’t get a glomerulonephritis in PAN

PAN associations:

• Hepatitis B > C

• HIV

• CMV

• Streptococcal infections

• IBD

Diagnosis (systemic PAN)

3 out of 10 criteria put out by ACR

Think of signs and symptoms first and then workup:

Investigations:

Blood pressure

Urinalysis

FBC (anaemia)

U&E

LFT

ESR/CRP

Hepatitis and HIV serology

ANCA (should be negative)

ASOT

Biopsy findings PAN:

LCV along with the arteritis of medium sized arterieis in the deep dermis and subcut tissue

May see a lobular panniculitis next to the involved vessels

Imaging:

• Renal angiogram to look for aneurysms or renal artery stenosis

Treatment:

• Immunosuppression:

◦ Systemic steroid for at least 6 months along with MTX or cyclophosphamide

• Organ specific management should involve other consultants (eg cardiology, nephrology)

• Treat any underlying causes (eg strep and Hep B)

KAWASAKI DISEASE

An acute febrile illness with vasculitis affecting the small and medium-sized vessels throughout the body, in particular the coronary arteries

Diagnostic criteria:

• Need fever of at least 5 days

and 4 out of 5 of other diagnostic criteria (Think CRASH and BURN)

• Burn= burning hot fevers > 39 celsius for five more days

Then four out of five of:

Conjunctivitis

Rash: polymorphous exanthem which can be peri-anal

Adenopathy: Cervical lymphadenopathy

Strawberry tongue or other oral changes

Hands/feet: erythema, oedema, eventual desqumation

Can also have:

Irritability, malaise, arthralgias

Uveitis

Gastroenteritis

Urethritis that may be symptomatic

Most cases are in children less than 5 years old

Especially around 10 months of age

Most patients have asian ancestry, especially Japanese kids

Coronary artery aneurysms can occur several weeks after symptom onset in about 25% of untreated children

These aneurysms are due to a medium vessel vasculitis

Lab investigation suspected Kawasaki disease:

FBC: WCC elevated, anaemia, thrombocytosis or thrombocytopaenia

U&E

LFT: Hypoalbuminaemia

CRP/ESR elevation

Nasal and throat swab looking for streptococcus

ASOT (As children with scarlet fever can have similar findings with fever, exanthem and strawberry tongue)

Blood culture

Urinalysis

Urgent ECHO looking for cardiac invovlement

Treatment:

Acutely ill:

IVIG 2g/kg over 12 hours as a single dose

Check IgA levels before to outrule IgA deficiency

If give IVIG to IgA deficienct patient they will see the IgA in IVIG as foreign and mount an immune reponse to it that can lead to anaphylaxis

High dose aspirin: 80-100mg/kg/day

This is the only time aspirin is acceptable to give to children

If patients fail to respond to IVIG and aspirin they may need:

Repeat IVIG treatment

Corticosteroids

Steroid sparing agents (ciclosporin or cyclophosphamide)

Behcet's disease

Inflammatory disease charachterized by recurrent oral apthous ulcers and numerous potential systemic manifestations

Many, but not all, clinical manifestations of Bechet disease are believed to be due to vasculitis

Among the systemic vasculitides, Behcets disease remarkable for ability to involve blood vessels of all sizes (small, medium and large) on both the arterial and venous sides of the circulation

Epidemiology:

Generally equal sex ratio

Affects young adults (20-40)

More common (and often more severe) along the ancient silk road from Eastern Asia to Mediterranean

Highest prevalence in Turkey (80-370 cases per 100,000)

US/Northern Europe (0.12-7.5 per 100,000)

Close relationship in geographic distribution of HLA-B51 and prevalence of BD

Odds ratio of developing BD with HLA-B51 +ve: 5.78

Aetiology and pathogenesis:

Underlying cause of Behcet syndrome unknown

As with other autoimmune diseases:

May represent aberrant immune activity triggered by exposure to an agent, perhaps infectious, in patients with a genetic predisposition to the disease

Genetic: HLA genes

Environmental influences: ? Abnormal immune response to microbes (eg Streptococcus or H pylori)

Clinical:

Mucocutaneous

Oral apthous ulcers

Painful, frequent, extensive

Urogential ulcers

Most specific lesion, less frequent, scar

Cutaneous (up to 75% of patients)

Acneiform lesions

Erythema nodosum

Pyoderma gangrenosum

Ocular (25-75%)

Anterior/posterior/pan uveitis

Retinal vasculitis

Optic neuritis

Neurologic disease (<10%, late onset, highly variable)

Parenchymal disease (brainstem, cerebrum, spinal cord)- wide range symptoms/signs

Non-parenchymal disease (meningism, cerebral venous thrombosis)

Vascular disease

Pulmonary artery aneurysm (Mortality approximately 25%) and thrombosis

Venous thrombosis (DVT, Budd-Chiari, Dural sinus thrombosis, SVC/IVC thrombosis)

Estimated 14-fold increased risk of venous thrombosis compared to controls

Arthritis

Non-erosive, aysmmetric, usually non-deforming

Gastro-intestinal

Abdominal pain, diarrhoea, bleeding (similar to IBD)

Renal and cardiac involvement

Infrequent but can occur

Pathergy:

Associated with Behcet’s disease

Is the development of cutaneous papulopustular lesions 24 hours after cutaneous trauma

More frequently positive in Behcet’s disease patients from endemic areas (50-75%) then non-endemic areas such as the US (10-20%)

Causes pathergy: Behcet’s, Pyoderma gangrenosum, Sweet’s syndrome

Diagnosis:

Behcet syndrome is best diagnosed in the context of recurrent apthous ulcerations along with characteristic systemic manifestations

There are no pathognomonic laboratory tests

Therefore diagnosis is made on the basis of clinical findings

Multiple diagnostic criteria exist:

One such example is the International Study Group Diagnostic Criteria (1990)

Another example is the International Criteria for Behcet’s Disease (ICBD, 2006)

Each of several findings are assigned a point value

Require at least 3 for diagnosis of Behcet’s